Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Or support our Kickstarter campaign!

Canada has quietly shifted into a new phase of EV focused industrial policy, not by announcing a dramatic ban or a sweeping mandate, but by changing the arithmetic that governs the automotive market. The federal government has moved away from explicit EV sales quotas and toward steadily tightening fleet average emissions standards, paired with open credit trading and a deliberate trade policy choice that allows large volumes of low cost electric vehicles to enter the country. Taken together, these moves create a system where outcomes are driven by math rather than slogans, and where capital flows predictably toward whoever can deliver the lowest emissions at scale.

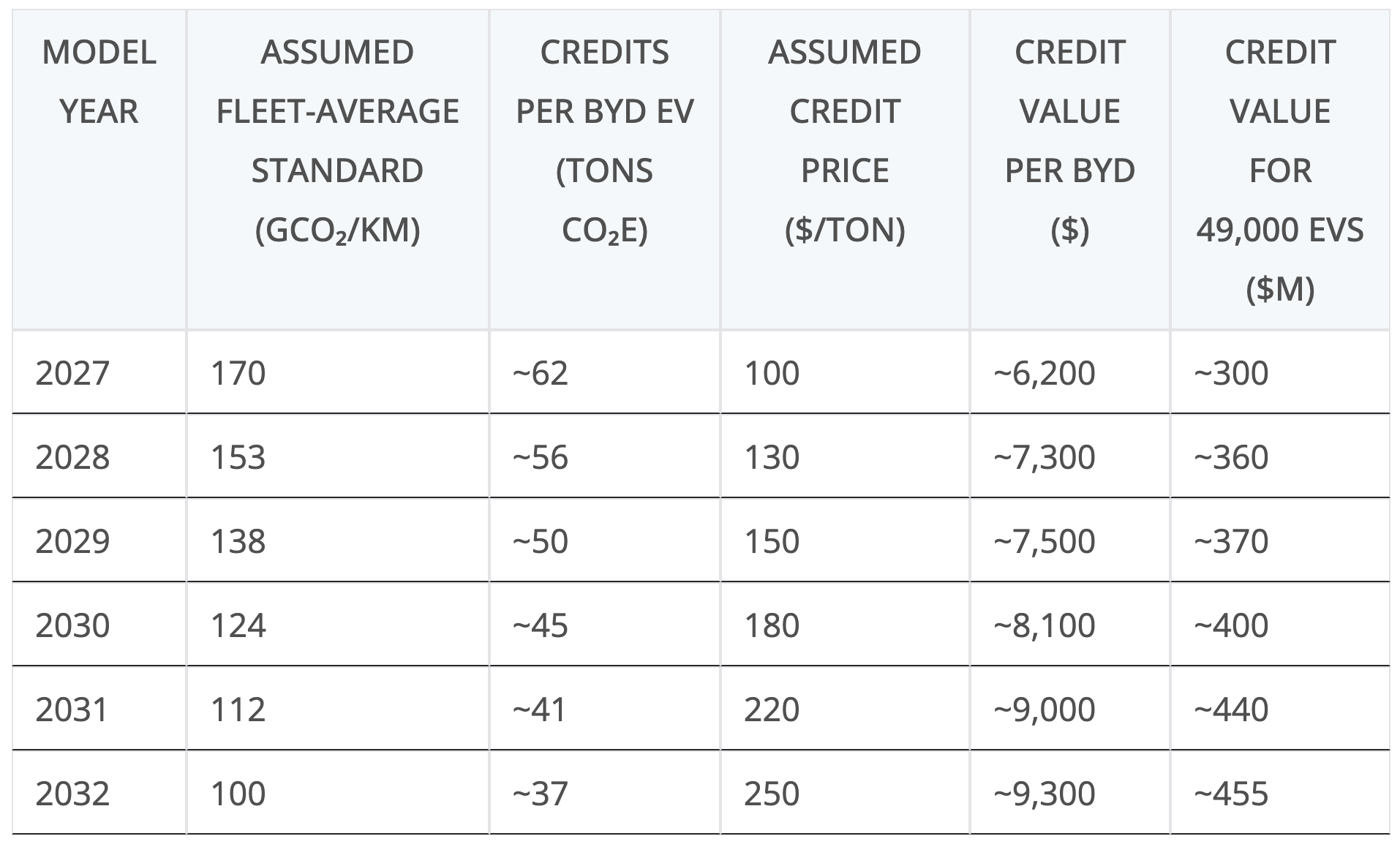

The core change is the tightening of fleet average greenhouse gas emissions standards starting in the late 2020s. Instead of requiring that a fixed percentage of vehicles sold be electric, the policy sets a blended emissions target across everything a manufacturer or importer sells in a given model year. Every Silverado, Equinox, Blazer EV, or imported crossover counts toward a single average. EVs count as zero. Internal combustion vehicles count at their certified grams of CO2 per km. The standard tightens annually, and while the exact post 2026 curve has not yet been published, a 10% year over year reduction is consistent with both international benchmarks and the government’s stated intent. That means a fleet average that might sit around 170 gCO2 per km in 2027 would need to fall to roughly 153 g in 2028, 138 g in 2029, and close to 100 g by 2032.

This matters because the compliance system is based on lifetime emissions, not annual tailpipe output. For light trucks, which include most SUVs and crossovers, the regulations assume roughly 225,000 miles of lifetime driving. Credits are calculated as the difference between the standard and actual emissions, multiplied over that lifetime distance. A zero emission vehicle sold into a fleet with a 170 gCO2 per km standard generates on the order of 60 tons of lifetime CO2 credits. Even at a more conservative 150 g standard, the number is still around 55 tons. These are not abstract numbers. They are the units that get traded between companies to balance compliance.

General Motors provides a useful example of how this plays out for a legacy manufacturer. In 2025, GM sold roughly 300,000 vehicles in Canada, with the vast majority being pickups and SUVs. EV sales were about 25,000 units, or roughly 8% of volume. Under current standards, that mix results in a compliance deficit that GM covers using banked credits and purchased credits, at a cost that works out to roughly $500 to $700 per vehicle depending on credit prices. That is manageable in the short term. The problem emerges as standards tighten. Under a 10% annual ratchet, GM would need roughly 20% to 30% EV share by 2027 to avoid buying credits, closer to 40% by 2029, and more than 50% by the early 2030s if the rest of its fleet remains dominated by large trucks. At constant sales of 300,000 units, that implies moving from 25,000 EVs to well over 100,000 within a few years. The math leaves little room for incrementalism.

At the same time, Canada has layered trade policy on top of this emissions framework by allowing up to 49,000 Chinese built EVs per year to enter the market at the standard 6.1% import duty instead of the previously announced 100% surtax. These vehicles are not treated as a special case in emissions accounting. If the Chinese OEM is the importer of record, its Canadian sales are assessed just like any other manufacturer’s fleet. Since those fleets are all electric, they massively over comply with the emissions standard and generate large volumes of tradable credits.

BYD is a representative example of how this changes the economics for new entrants. Take a small electric SUV, similar to the Atto 3, sold into Canada in 2027. As a crossover, it is likely classified as a light truck for regulatory purposes. At a 170 gCO2 per km standard, that single vehicle generates roughly 62 tons of lifetime emissions credits. If credit prices sit in a plausible early tightening range of $80 to $120 per ton, the credit value per vehicle is roughly $5,000 to $7,400. Against that, BYD pays a 6.1% import duty. If the value for duty is $30,000, the tariff cost is about $1,830. The net policy driven benefit before any other costs or margins is still on the order of $3,000 to $5,500 per vehicle.

Scaled up to the full annual quota, the numbers become material. Forty nine thousand EVs generating roughly 55 to 62 tons of credits each translates into 2.7 to 3.0 million tons of credits per year. At $100 per ton, that is about $300 million in potential credit value. Even after paying roughly $90 million in import duties on $30,000 vehicles, the net remains well over $200 million. This is not a rounding error. It is a structural revenue stream created by the interaction of emissions policy and trade rules.

It is also important to note what is not happening. These credits are not handed out by the government. They are earned by selling zero emission vehicles into a tightening regulatory environment. They represent avoided lifetime emissions compared to the standard. When General Motors or another legacy OEM buys those credits, it is not subsidizing China in an abstract sense. It is paying for real emissions reductions that it has not yet delivered itself. The money flows from firms with emissions intensive fleets to firms with clean fleets, exactly as the policy is designed to encourage.

Over time, the balance shifts. Credit prices are likely to rise as standards tighten and banked credits are exhausted. Reasonable expectations place early prices in the $80 to $120 per ton range, rising toward $150 to $250 by the early 2030s if EV adoption does not accelerate fast enough to flood the market with credits. At those levels, per vehicle compliance costs for lagging OEMs move from hundreds of dollars to well over $1,000. Buying time becomes expensive.

The strategic implication is straightforward. Canada has created a system where legacy automakers can pay for compliance in the short term, including paying EV only manufacturers like BYD, but only while they rebuild their product mix. The longer they delay, the more money flows outward and the higher the eventual adjustment cost becomes. There is no stable equilibrium where a truck heavy fleet can indefinitely buy its way out. The arithmetic closes that door.

Politically, this shift works in Carney’s favour. By removing the explicit EV sales mandate, he eliminates the most visible and easily attacked element of the previous policy framework. Mandates are simple to caricature and invite arguments about bans, consumer choice, and government overreach. Replacing that headline target with a tightening emissions standard changes the nature of the debate in a way that is far less emotive.

What takes the mandate’s place is a market mechanism that is harder to argue with in public. Fleet-average emissions standards and tradable credits frame the transition as an outcome to be achieved rather than a behaviour to be enforced. Automakers are not told what vehicles to sell. They are told the emissions result they must meet, with flexibility in how they get there. Opponents are left arguing against emissions accounting and market pricing rather than against an explicit quota.

This approach also disperses political responsibility. If EV adoption accelerates, it can be attributed to falling prices, competition, and innovation rather than government compulsion. If legacy automakers complain about rising compliance costs, the response is that they retain multiple options, including changing their sales mix, investing faster, or buying credits from others. The state is no longer visibly picking winners, even though the structure clearly rewards zero-emission vehicles.

It also has the potential to force the transition just as quickly as the mandate it replaces, even if it looks softer on the surface. A steadily tightening fleet-average emissions standard produces a similar outcome once the numbers drop below what internal combustion vehicles can plausibly deliver at scale. At that point, the only practical way to comply is to sell a rapidly growing share of zero-emission vehicles.

In practice, the pressure can be stronger than a simple sales quota. A mandate fixes a percentage and leaves room for lobbying, delays, or carve-outs. An emissions standard that tightens every year compounds. Each year of delay increases the number of EVs required later, while also increasing the cost of buying compliance from others. The arithmetic does not pause, even if product cycles do.

Because the system prices lifetime emissions, the financial signal is front-loaded. Credits represent decades of avoided emissions, so shortfalls accumulate quickly and become expensive. That creates an incentive to move early rather than wait for the last compliant year. From an automaker’s perspective, missing the curve by a few years can be far more costly than missing a one-time mandate target.

The result is that, while the policy avoids the rhetoric of compulsion, it still delivers compulsion through economics. Automakers retain theoretical choice, but the cost of choosing not to electrify rises year by year. In that sense, the new framework does not slow the transition. It channels it through market forces in a way that can be just as decisive, and in some cases more relentless, than an explicit mandate.

There is also an affordability narrative embedded in the shift that works to Carney’s advantage. By pairing emissions standards with openness to lower-cost EV imports, the government can credibly argue that it is expanding choice rather than constraining it. Instead of telling Canadians what they must buy, the policy creates conditions where inexpensive electric vehicles are more likely to be available, including models that domestic automakers have been slow to offer. That allows Carney to frame the transition not as a sacrifice imposed on households, but as a way to make cleaner transportation cheaper and more accessible, a message that resonates far more broadly than climate targets alone.

Finally, the shift makes the policy more durable. A sales mandate can be repealed quickly by a future government. A market-based system embedded in regulations, credit banks, and multi-year compliance planning is much harder to unwind without creating disruption. Once companies have internalised the emissions curve into their investment decisions, reversal becomes costly. In that sense, removing the mandate does not weaken the policy. It strengthens it by making it stick.

Publicly, the response from legacy automakers and their representative organizations has been broadly positive. Groups such as the Canadian Vehicle Manufacturers’ Association have welcomed the shift toward fleet-average emissions standards as more flexible and more aligned with market realities. The emphasis in their statements is on optionality, predictability, and the ability to respond to consumer demand rather than comply with a fixed quota that could create inventory risk.

That reaction reflects a particular way of thinking about cost and risk. An emissions standard feels easier to manage than a mandate because it spreads obligation across the entire fleet and across time. Compliance is no longer binary in a given year. Instead of missing a percentage target, companies can partially comply and make up the difference with credits. As long as credit prices remain moderate, this converts what would have been a hard constraint into a line item. In the late 2020s, paying several hundred dollars per vehicle in credit costs looks cheaper and less disruptive than accelerating platform transitions, retooling plants, or pushing EV volumes faster than dealers believe the market can absorb.

There is also comfort in the range of levers available. Under an emissions framework, legacy OEMs can lean on incremental efficiency gains, hybrids, modest mix shifts, and purchased credits, rather than relying almost entirely on EV sales growth. That flexibility lowers perceived near-term risk and makes it easier to reassure boards, investors, and dealers that the transition can be paced and managed rather than rushed.

The danger is that this logic holds only in the short term. The emissions standard tightens every year, not every product cycle. Each year of slower EV uptake increases the EV share required later and increases the volume of credits that must be bought in the meantime. Because the system prices lifetime emissions, deficits accumulate quickly. What looks like a manageable operating cost in the late 2020s can become a structural cost problem in the early 2030s as standards tighten and credit prices rise.

There is also a collective blind spot. Credit markets stay cheap only if enough manufacturers over-comply. If most legacy OEMs make the same rational short-term choice to buy time instead of accelerating EV sales, demand for credits rises faster than supply and prices move accordingly. At that point, the emissions framework becomes more expensive than the mandate it replaced, not less. The policy gives legacy automakers flexibility, but it also charges them for every year they use it. In the medium term, that makes delay riskier than it appears today.

What looks at first glance like a collection of disconnected policies is in fact a coherent, if understated, industrial strategy. Tighter emissions standards create demand for credits. Open credit trading determines who gets paid. Trade policy choices influence who supplies those credits and at what cost. The outcome is that legacy OEMs must significantly up their EV game, and until they do, they will be paying firms like BYD for the privilege of continuing to sell high emitting vehicles in a market that has decided, quietly and numerically, to move on.

Support CleanTechnica via Kickstarter

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy