The recent explosion in large language model (LLM) technology has highlighted the challenges of using public generative artificial intelligence (AI) tools in classified environments, especially for software analysis. Currently, software analysis falls on the shoulders of heuristic static analysis (SA) tools and manual code review, which tend to provide limited technical depth and are often time-consuming in practice. As this post details, a group of SEI researchers sought to prove that LLMs can be used in unclassified environments to rapidly develop tools that could then be used to accelerate software analysis in classified environments. The resulting tools were a plugin-based architecture that enables analysts to develop customer checkers (i.e., plugins) and a visualization tool that leverages CodeQL to perform control flow and taint analysis to help analysts perform CSA. The tools created an initial time savings of approximately 40 percent and improved accuracy of approximately 10 percent, based on experiments conducted with a team of software analysts.

In this blog post, adapted from a recently published paper, we highlight our approach, which can be used to develop static analysis tools in classified and unclassified environments, as well as the two existing tools. This work is part of ongoing SEI research to apply artificial intelligence (AI) across software engineering activities, including software analysis.

Issues with Static Analysis Tolls in the Software Development Lifecycle

While LLMs are relatively new, SA tools have long been present in the software development lifecycle. Despite their utility, out-of-the-box heuristic SA tools often fail to provide the quality analysis required for complex systems. These SA tools tend to use pattern matching and other approximate techniques and lack full comprehension of code semantics, leading to gaps in the depth of their analysis. Conversely, manual code review, despite its effectiveness in identifying issues that automated tools might miss, is time consuming, demanding of human attention, and scales poorly with the size of modern software projects. These shortcomings present a significant bottleneck in the SDLC, impacting the speed and quality of software delivery.

To resolve these bottlenecks, we sought to demonstrate how LLMs can be used to develop tools that streamline traditionally manual aspects of software analysis. Unlike existing research on directly applying LLMs to software analysis tasks, our research suggests that leveraging public LLMs (i.e., an internet accessible, commercial/open-source model such as ChatGPT) for SA tool generation offers increased efficiency and a greater technical depth for software analysis tasks. Our work focused on improving code verification in classified environments (i.e., any area that handles sensitive information and/or has an air-gapped network).

Issues with LLMs in Software Analysis

LLM-generated code can be error-prone, which highlights the need for robust verficiation and testing frameworks. LLM reliability issues are particularly concerning when LLMs are applied to critical tasks, such as vulnerability and quality analysis. These sophisticated tasks often require a contextual understanding of software’s logic and execution flow. LLMs, constrained by their training data, often lack the subject matter expertise of trained software professionals and may fail to fully grasp the intricacies of complex systems. For example, experiments by researchers in the SEI CERT Division’s Secure Development initiative demonstrated the limitations of LLMs in identifying and correcting C code that was noncompliant with a coding standard.

A Methodology for Incorporating LLMs in Static Analysis Tool Development

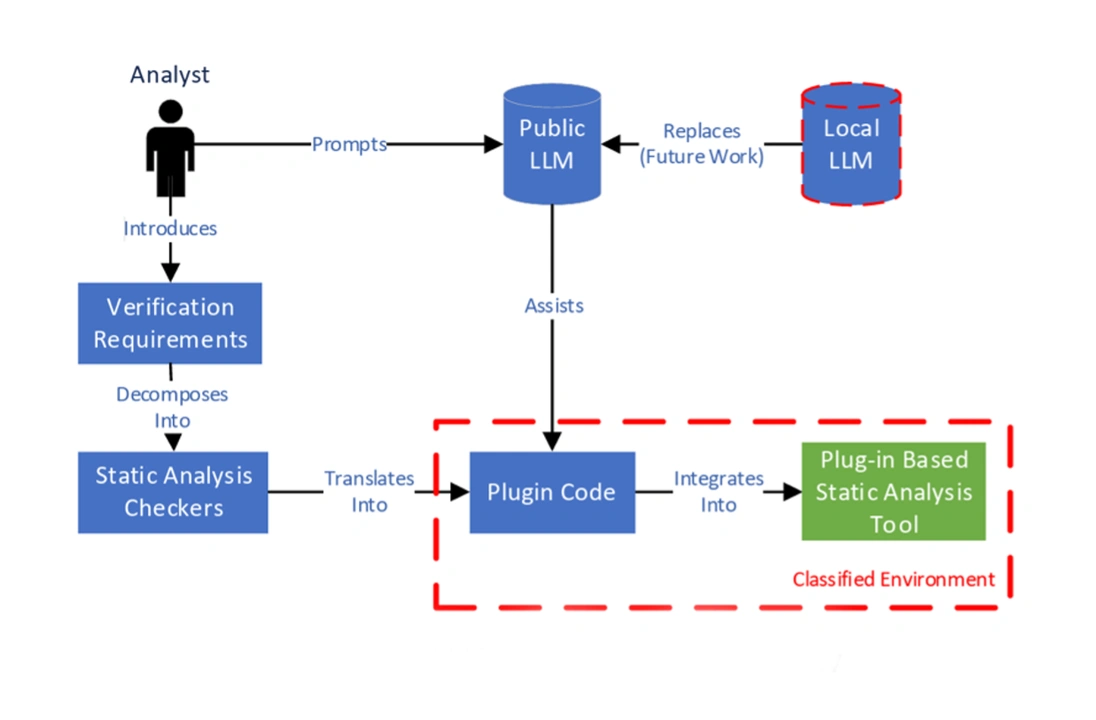

Although there has been a great deal of work on the efficacy of LLMs for direct software analysis, their current limitations prompted us to investigate their utility in developing tools for software analysis. This new research direction leverages natural language prompting to allow LLMs to assist with developing SA tools that can operate in classified environments. In addition, it allows end users with minimal software experience to customize SA tools.

In our methodology, we input public (i.e., openly published) material related to software verification tasks into public LLMs, and used them to assist in the design, implementation, and customization of SA tools. We later reviewed and migrated the resulting tools to a classified environment. Needless to say, software tools developed using our approach must be reviewed as described in software security verification standards before being deployed in classified environments.

The specific policies for reviewing software before deployment on a classified system follow government regulations and are generally proportional to the level of required security. Although these security reviews must still be performed with our approach, our use of LLMs to create SA tools provides significant control over the software deployed in a classified environment.

We found that our methodology can be used to generate SA tools for unclassified environments as well. In such cases, the public LLM could have access to the codebase, test cases, and software output, potentially increasing its value in generating SA tools. Our methodology can be split into two different workflows:

- a tool developer workflow

- a software analyst workflow

Figure 1 shows the workflow for a tool developer.

Figure 1: AVASST Tool Developer Workflow

In this workflow, the tool developer collaborates with software analysts to develop a set of software requirements (e.g., quality attributes, programming paradigms) that drive the prompts fed into a public LLM. The LLM is then used to help design tool architectures from which a tool developer can down select based on the analysts’ priorities (e.g., efficiency, maintainability). Once the final architecture is selected, the LLM can help tool developers implement various prototypes, from which the tool developer can further down-select based on quality attribute requirements (e.g., interoperability, scalability).

Upon completion, tool developers should have a tool that can help to verify some or all the requirements that encompass the verification task. To test the tool, developers can use a variety of approaches, including using an LLM to generate test code. After rigorously testing the generated SA tool, it can be safely deployed in a classified environment. In a case study, we applied this workflow and leveraged an LLM to quickly iterate through various prototype architectures for a SA tool. After down selecting to a plugin-based architecture, which could facilitate the seamless integration of future tool expansions, we leveraged LLMs to help us implement our SA tool.

Figure 2 shows the workflow for a software analyst.

Figure 2: AVASST Analyst Workflow

In this workflow, a software analyst leverages a public LLM to decompose the previously developed requirements into a suite of plugins (i.e., SA checkers). Once these plugins are migrated to a classified environment, they can integrate into our previously developed SA tool. Then, analysts can run the enhanced SA tool over classified code and use its output to help verify a codebase meets specified requirements.

Our methodology is iterative, enabling analysts to customize existing plugins to increase their efficacy and develop new plugins to fit the changing needs of their organization. In Figure 1 and Figure 2, a red dotted boundary highlights the tools or activities that can be transitioned into classified environments. Future research might involve the introduction of a local, on-premises LLM into the classified environment to expand the classified boundary and potentially improve the efficacy of our workflows.

Using Our Methodology to Create Static Analysis Tools

To demonstrate the effectiveness of our hybrid methodology, we developed a set of custom SA tools and collaborated with software analysts working in a classified environment. From discussions with analysts, we found two primary pain points that were significantly impacting their productivity:

- government software requirements validation involves validating that software complies with government safety and/or security requirements

- critical signal analysis (CSA) involves verifying the integrity of safety critical data as it flows through the program.

We leveraged our methodology to develop two custom SA tools in these two areas:

- AVASST Plugin Suite is a tool with a plugin-based architecture that enables analysts to develop custom checkers (i.e., plugins) using the Clang-Tidy framework to help verify government software requirements.

- FlowFusion is a visualization tool that leverages CodeQL to perform control flow and taint analysis to help analysts perform CSA.

The AVASST Plugin Suite leverages Clang-Tidy to provide custom SA checkers for analysts. Clang-Tidy is a linter tool for C and C++ that is built on top of the Clang compiler frontend. It is used to perform SA on code to catch errors, enforce coding standards, and suggest improvements. It includes a library of standard checkers out-of-the-box and supports the creation of custom checkers that search for structural features of the compiled software’s abstract syntax tree (AST) via the ASTMatcher library. We leveraged LLMs to assist with our understanding of the ASTMatcher library and generate skeleton code for using existing Clang-Tidy checkers.

Then we used LLMs to iteratively develop a plugin architecture that supports the simple integration of future LLM- or human- generated custom checkers. We also used LLMs to help evaluate the viability of existing Clang-Tidy checkers for validating government software requirements. Where we found gaps, we prompted LLMs to help us translate high-level software requirements into ASTMatcher queries. This helped us develop an initial set of custom checkers for validating the integrity of message data.

LLMs also helped us develop a Command Line Interface (CLI) and GUI to enhance usability and allow users to graphically combine checkers into groups to verify selected government software requirements.

CodeQL, a tool developed by GitHub, uses a proprietary AST parser and other techniques to statically analyze a codebase and provide a query language to enable users to search for structural code features that manifest in an AST. CodeQL can be used to perform taint analysis—the tracking of data that has been influenced (i.e., tainted) by an external, potentially untrusted source as it flows through a program. Taint analysis can be used to detect vulnerabilities such as injection attacks, where tainted data affects sensitive parts of a program lacking proper input validation. We leveraged LLMs to assist with the development of CodeQL taint analysis queries that track critical signals flowing through the software. However, taint analysis alone only provided a narrow view of the critical signal pathway. Analysts found that there were additional function calls and conditions involving untainted data that were not fully captured but still important for a thorough CSA. This was not a flaw in the concept of taint flow, which is not designed to track untainted data. Nevertheless, we needed to incorporate additional information into our tool’s output for it to be useful for analysts. Thus, we proposed FlowFusion, the novel concept of overlaying a taint flow graph on top of a control flow graph. FlowFusion offered a more complete picture of the critical signal pathway and enabled analysts to proceed with more confidence in their analysis. Figure 3 shows a FlowFusion visualization containing grey rectangle and orange oval nodes. The grey rectangles represent functions, and edges between rectangles represent control flow. In addition, the orange ovals represent tainted data, and edges between them represent taint flow.

Figure 3: Example Visualization from FlowFusion

The various graph nodes are also interactive, allowing users to navigate to the exact code locations visualized in the graph by simply clicking on a node. By combining the control and taint flows into an interactive overlay visualization, analysts can have a more comprehensive view of the pathway critical data takes through the program and accelerate their verification of software requirements. While research in human-AI teaming suggests we may be able to introduce LLMs to assist analysts with the red tasks, we did not pursue this direction due to time constraints but plan to in future work.

Limitations and Impact of Our Approach

Although our work represents a step forward in improving software analysis, it does have some limitations. First, recall that even best-in-class, public SA tools often cannot fully verify requirements. Similarly, we should not expect our custom tools to provide a cure-all solution. However, our tools did provide some acceleration in requirements verification.

Second, our tools require analysts to know the structural features they wish to search for in the codebase. However, analysts unfamiliar with a codebase may not know what to search for a priori, making it difficult to construct high-quality queries.

Third, our approach requires a human-in-the-loop to verify that the tool outputs are accurate, since LLMs were used to create the tools and LLM reliability issues (e.g., hallucinations) can sometimes lead to inaccurate output. The tools themselves can also output false positives or false negatives that require human adjudication, like most SA tools.

A Common Platform for Sharing Custom LLM-Generated Plugins

To evaluate the long-term usefulness of our tools, we delivered them to an in-house team of analysts for use during software analysis tasks. These tasks traditionally require extensive manual effort, which is both time-consuming and prone to human error. We hope that our LLM-augmented tools significantly speed up the analysis process and produce a higher degree of accuracy than traditional methods.

We expect our tools to enhance collaboration and consistency among team members by providing a common platform for sharing custom LLM-generated plugins. In addition, we project that efficiency gains achieved through our tools will extend across the entire SDLC. As analysts receive multiple versions of software over time, our tools should enable them to quickly replicate specific analysis checks and analyze changes between each version; a manual analysis of changes would likely prove more time consuming. While we await long-term efficacy results, we have developed some initial confidence in our tools through preliminary experimentation and surveys.

Future Work Using LLMs in Software Analysis

The AVASST Plugin Suite and FlowFusion represent a step forward in tailoring analyses to assure compliance with special requirements such as CSA . Our case studies demonstrate how LLMs can be successfully integrated into software analysis processes to enhance productivity, especially in classified environments, which have unique connectivity and confidentiality constraints.

Many opportunities exist to expand upon our research including:

- Developing standards for evaluating SA and LLM-assisted software development: To the best of our knowledge, there are no suitable standard metrics or test data sets for evaluating the efficiency or accuracy of our SA tools or methodology. Future work could explore developing a standard to compare our work to existing techniques.

- Customizing LLM solutions for different programming paradigms: Our current prompt engineering guidelines, which we detail in our paper, are tailored to specific code generation tasks (i.e., plugin-based architecture). Future work could focus on integrating continuous learning mechanisms or more flexible prompt engineering techniques to tune LLMs to generate code that follows other design patterns (e.g., microservices).

- Integrating human-AI teaming: New research in the field of human-AI teaming suggests we may be able to introduce LLMs into tasks that require human intervention to further accelerate analysis workflows. Future work can investigate best practices for incorporating human-AI teaming into workflows constrained by the unique requirements of classified environments.