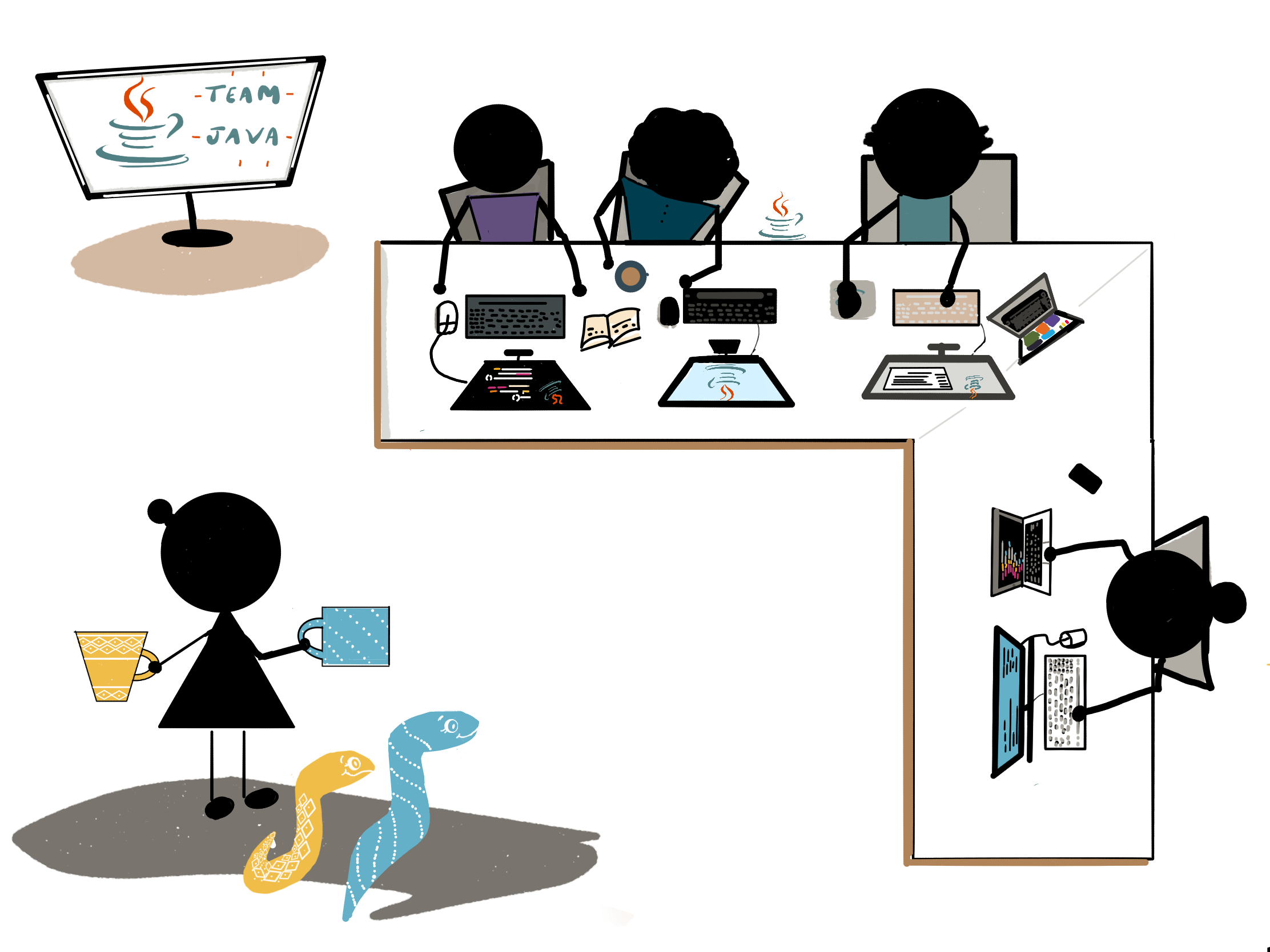

Writing a sophisticated computer program often requires a lot of detailed

knowledge. If we do this in Java, we need to know the syntax of the

language, the wide range of libraries available to assist us in the work,

the various tools required to verify and build our programs. If we do this

in Python instead, we are faced with a different syntax, libraries that are named

and work differently, a whole other ecosystem to build and run our work.

Faced with these details, a natural response is to recruit people who

are knowledgeable about a specific ecosystem. Thus we see job descriptions that say “at

least three years of Java”, or even deeper requirements for subsets of that

community, with experience in specific tools. What use is a skilled

Python programmer to such a team?

We’ve always felt that such desires are wrong-headed. The characteristics

that we’ve observed separating effective software developers from the chaff

aren’t things that depend on the specifics of tooling. We rather appreciate

such things as: the knowledge of core concepts and patterns of programming, a

knack for decomposing complex work-items into small, testable pieces, and the

ability to collaborate with both other programmers and those who will

benefit from the software.

Throw such a Python programmer into a Java team, and we’d expect them to

prosper. Sure they would ask a lot of questions about the new language and

libraries, we’d hear a lot of “how do you do this here?” But such questions

are quickly answered, and the impediments of Java-ignorance soon wither

away.

An experienced Pythonista who understands

the core patterns and practices of software development can be a productive

member of a team building software in Java. Knowing how to handle

snakes can be surprisingly handy.

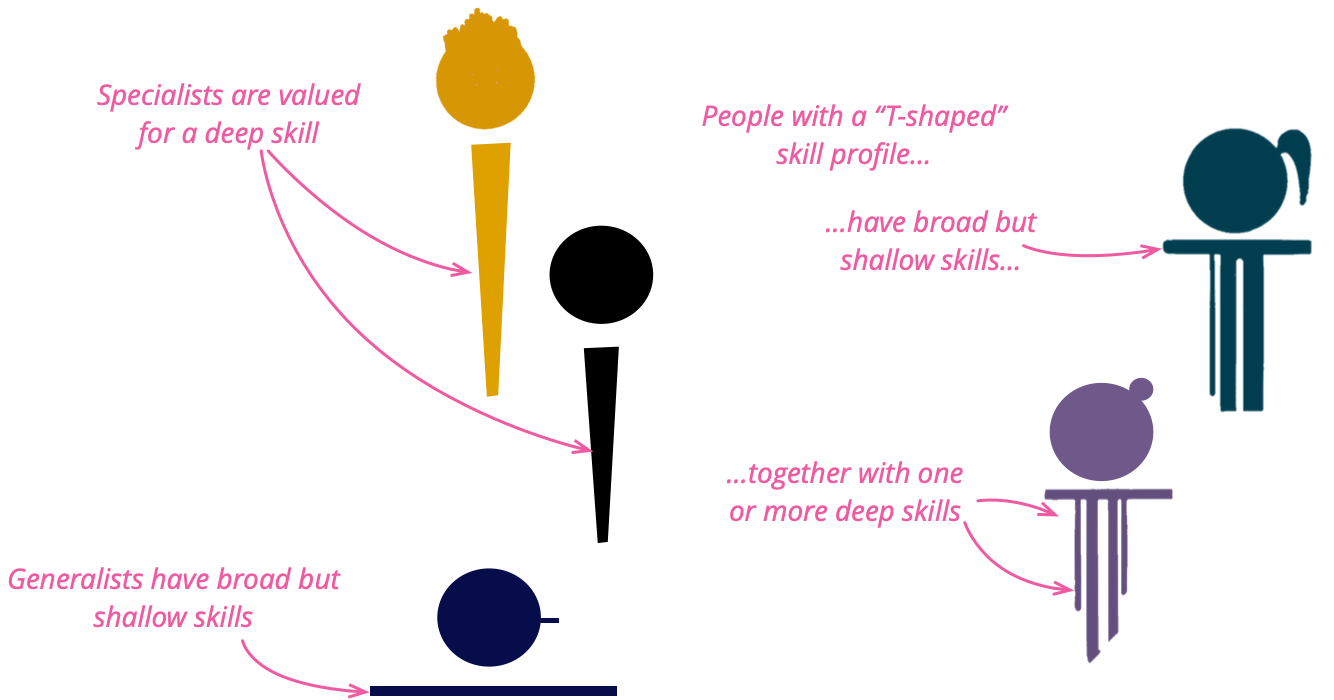

This echoes a long debate about the relative value of specialists and

generalists. Specialists are seen as people with a deep skill in a specific

subject, while generalists have broad but shallow skills. A dissatisfaction

with that dichotomy led to the idea of “T-shaped people”: folks that combine

deep knowledge in one topic, with a broad but shallow knowledge of many

other topics. We’ve seen many such people quickly grow other deep legs,

which doesn’t do much for the “T-shape” name (as we’ll discuss below), but otherwise leads to

success. Often experience of a different environment leads to trying things

that seem innovative in a new home. Folks that only work in a single

technological neighborhood are at the constant risk of locking themselves

into a knowledge silo, unaware of many tools that could help them in their

work.

This ability goes beyond just developer skills. We’ve seen our best

business analysts gain deep skills in a couple of domains, but use their

generalist skills to rapidly understand and contribute in new domains.

Developers and User Experience folks often step outside “their lanes” to

contribute widely in getting work done. We’ve seen this capability be an

essential quality in our best colleagues, to the degree that its importance

is something we’ve taken for granted.

But increasingly we see the software industry push for

increasing, narrower specialization.

So over the last year or so we have started to resist this industry-wide

push for narrow skills, by calling out this quality, which we call an

Expert Generalist. Why did we use the word “expert”?

There are two sides to real expertise. The first is the familiar depth: a detailed command

of one domain’s inner workings. The second, crucial in our fast-moving field

is the ability to learn quickly, spot the

fundamentals that run beneath shifting tools and trends, and apply them wherever we land.

As an example from software teams, developers who roam across languages, architectures, and problem spaces may seem like

“jack-of-all-trades, master-of-none,” yet repeated dives below surface differences help them

develop durable, principle-level mastery. Over time these generalists can dissect unfamiliar

challenges, spot first-principles patterns, and make confident design decisions with the

assurance of a specialist – and faster. Being such a generalist is itself a

sophisticated expertise.

We’ve long noticed that not just anyone succeeds as an Expert Generalist,

but once we understand the traits that are key for such Expert Generalists,

organizations can shape learning programs, hiring filters, and career paths

that deliberately develop them. Indeed our hiring and career progression at

Thoughtworks has been cultivating this skill for over two decades, but doing

so informally. We think the industry needs to change gears, and treat Expert

Generalist as a first-class skill in its own right: something we name,

assess, and train for. (But beware, we find many Expert Generalists,

including at least one author of this article, cringe at the word “expert”.)

The Characteristics of an Expert Generalist

When we’ve observed Expert Generalists, there are certain attributes

that stand out.

Curiosity

Expert Generalists display a lot of curiosity. When confronted with a new

technology or domain, their default reaction is to want to discover more about it, to see

how it can be used effectively. They are quite happy to spend time just exploring the new

topic area, building up some familiarity before using it in action. For most, learning new

topics is a pleasure in itself, whether or not it’s immediately

applicable to their work.

This characteristic is noticeable when Expert Generalists get an answer

to a question. Rather than just typing in some code from Stack Overflow,

an Expert Generalist’s curiosity usually motivates them to ensure they

understand the answer, taking the opportunity to expand their knowledge,

and check that the answer they got is appropriate. It’s also present when

asking a question. There is an art to asking questions that elicit deeper

answers without leading the witness.

Collaborativeness

Learning about a new topic area may require reading, watching videos, and prototyping. But

we see the greatest aid here is another vital characteristic: collaborativeness.

A wise Expert Generalist knows that they can never really learn about most of the things

they run into. Their T-shape will grow several legs, but never enough to span all the

things they need to know, let alone want to know. Working with people who do have those

deeper skills is essential to being effective in new domains.

Working with an otherly-skilled worker allows the generalist to

contribute while the skilled collaborator spots more effective paths that

only a specialist would know. The generalist appreciates these

corrections, learning from them. Learning involves both knowing more about

the new domain, but also learning to differentiate between areas where the

generalist can do primary contributions and areas where the generalist

needs help from the specialist. We notice Expert Generalists are never

afraid to ask for help, they know there is much they are ignorant of, and

are eager to involve those who can navigate through those areas.

An effective combination of collaborative curiosity requires

humility. Often when encountering new domains we see things that don’t

seem to make sense. Effective generalists react to that by first

understanding why this odd behavior is the way it is, because there’s

usually a reason, indeed a good reason considering its context. Sometimes,

that reason is no longer valid, or was missing an important consideration

in the first place. In that situation a newcomer can add considerable

value by questioning the orthodoxy. But at other times the reason was, and

is still valid – at least to some extent. Humility encourages the Expert

Generalist to not leap into challenging things until they are sure they

understand the full context.

This humility extends to recognizing the different trade-offs we see

across architectures. An architecture designed to support large volumes

of simple transactions will differ from one designed to handle a few

complex interactions. Expert Generalists are comfortable in a world where different

trade-offs make sense in different circumstances, usually because their

travels have exposed them to these differences.

Customer Focus

This curiosity and eagerness to collaborate with people with different skills does raise a

danger. Someone driven by curiosity can chase every shiny object. This is where the

characteristic of customer-focus comes into play. We are often impressed with

how an Expert Generalist takes each unfamiliar technology and questions how it helps the

customer. We are fans of Kathy Sierra’s notion that our purpose as software developers is to help our

customers become “badass” at what they do.

Customer-focus is the necessary lens to focus curiosity. Expert

generalists prioritize their attention on the things that will help them

help their users to excel. This encourages learning about what their

customers do, and how they can improve their work. It focuses attention on

technologies that contribute to building those things. Customer-focus

energizes collaboration, encouraging the exchange of information between

customer and technologist, and allowing the Expert Generalist to

coordinate other technologists towards enabling the customers’

excellence.

Favor Fundamental Knowledge

Software development is a vast field, where nobody can know everything, or even a

reasonable fraction of everything, so we all need to prioritize what topics we learn. Expert

Generalists favor fundamental

knowledge, that doesn’t become outdated with changes when platforms update. These are

often expressed as patterns or principles. Such knowledge tends to age slowly, and is

applicable when folks move into new environments. For example the basic moves of refactoring

are the same whatever language you are programming, the core patterns of distributed systems

reappear regularly (and it’s no coincidence that’s why we wrote books on those topics – we

like book sales that last for many years).

Blend of Generalist and Specialist Skills

Thus generalists often have deep knowledge of fundamentals, and we usually see them have

deep knowledge of a few other topics too. They combine a broad general skill with several

areas of deeper knowledge, usually acquired as it’s necessary for products they’ve worked

on, coupled with the curiosity to dig into things that puzzle most people. These deeper

areas may not be relevant to every engagement they work on, but is a signal for their acumen

and curiosity. We’ve learned to be suspicious of people who present as a generalist yet

don’t have a few deep specialties.

We mentioned before that a common name for this skills profile is that

of the “T-shaped” person, implying a blend of specialist and generalist

skills. While the T-shape moniker did catch on, it comes with a

major problem in the metaphor, we don’t find such folks have only a

single deeper skill. They usually have a few, of varying depth. We’re not

the only people to identify this problem, and there have been several

other names proposed to describe this skill-set, although the alternatives

all have their own problems.

The vertical stroke of a skill set represents broader, long-lasting

domains, not specific tools or frameworks. An expert generalist therefore pursues depth

in distributed-data systems—partitioning and replication strategies, fault-tolerance

mechanisms, consistency models, and consensus algorithms—instead of mastering only

Databricks notebooks. In the cloud, they focus on cloud-native architecture: auto-scaling

heuristics, multi-region fail-over etc rather than

focusing on AWS-specific configuration syntax. On the front end, they study browser-based

UI architecture—rendering pipelines, state-reconciliation patterns, and accessibility

primitives—instead of the latest React APIs.

Sympathy for Related Domains

Expert generalists often find themselves in unfamiliar territory—be

it a new software stack, a new domain, or a new role. Rather than chasing

exhaustive detail from day one, they cultivate a rough, perceptive sense of

what works in the new environment. That helps them make choices that

go with the grain—even when it differs from their previous experience.

Jackie Stewart, a triple Formula 1 world champion (1969-93),

described how, while he wasn’t an engineer of the cars he drove, he

still needed a sense of how they

worked, how they responded to what the driver was trying to do, a

sense he called mechanical sympathy.

Martin Thompson brought this

concept into software, by talking about how a similar knowledge

of how computer hardware works is vital to writing high-performance

software.

We think that the notion of mechanical sympathy has a broader

sense in software, in that we do need to cultivate such a

sympathy for any adjacent domain to the ones we are working on. When

working on a database design, we need such a sympathy for the

user-interface so we can construct a design that will work smoothly with

the user-experience. A user-experience designer needs such a sympathy

with software constraints so when choosing between similarly valuable

user flows, they take into account how hard it is to build them.

This also shows itself with new teams. When joining a new team, expert

generalists tend to listen to the established ways that a team works,

introducing different approaches thoughtfully. Even when coming in as

leaders, they don’t default to tearing up existing workflows in favor of

those more familiar to them. Their curiosity extends to understanding why

different people work in different ways, trying out unfamiliar working

styles, then incorporating their experience to develop practices to

improve from the current state.

Assessing Expert Generalists

We have two crucial checkpoints for spotting —and then nurturing

—expert generalists: the hiring interview and ongoing career

progression.

Hiring

Traditional interview loops still revolve around product

trivia—“Explain Spark’s shuffle stages,” “How does Databricks Delta

time-travel work?” A candidate who has never touched those tools can

still be exactly the kind of person we need: someone who quickly

grasps unfamiliar concepts, breaks complex systems into manageable

parts, and collaborates across functions. Focusing on a single stack

or cloud provider risks filtering out such talent.

To surface that potential, widen the conversation beyond tool

recall. Ask candidates to talk through past experiences:

- How did they approach a particularly challenging situation?

- When have they ventured into an unfamiliar domain, and how did

they get up to speed? - How do they collaborate with people inside and outside their own organisation or

discipline?

These stories reveal learning velocity, systems thinking,

and people skills—the raw material of an expert generalist.

Example · Process-control engineer We once met an engineer

whose entire résumé was industrial PLC work—no general-purpose

language, no web, no cloud. Yet his record of diagnosing

control-system failures and the questions he asked during the

interview showed exceptional learning agility. Hired for those

qualities, he grew into a respected technical leader and later a

product owner. Rejecting him for not knowing “our” tools would have

been a costly miss.

Career progression

Inside the organisation, narrow verticals can freeze growth: UI

developers, QAs, data engineers, or cloud experts seldom step

outside their lanes. The growth paths map one-to-one with vertical

silos: UI Engineer → Senior UI Engineer → UI Architect, or Data

Engineer → Senior Data Engineer → Principal Databricks Guru. The

unintended message is, “wander outside your lane and your progress

stalls.

We have found that encouraging people to experiment—letting them

make mistakes and learn in adjacent disciplines—yields remarkable

benefits. A business analyst writing code out of curiosity, a

front-end engineer dabbling in DevOps, a data engineer trying

product analysis: each cross-pollination broadens both the

individual and the team.

Example · Medical-domain analyst A non-technical professional

from healthcare joined us as a business analyst. His passion for

tech pulled him into code reviews and pairing sessions. Over time he

became an outstanding tech lead and a broader strategic thinker than

many traditional “pure” engineers.

Both stories underscore the same lesson: if we base assessment and

advancement solely on a checklist of tools, we forfeit the chance to

work with brilliant, adaptable people—and we hamper the organisation’s

ability to innovate.

Growing Expert Generalists

From Tools to Fundamentals

IT trends get triggered by pivotal inventions that enable new business

opportunities. Product providers and tool vendors quickly build products,

and the industry focus often shifts to expertise in tools and frameworks

rather than the underlying technical trends. For example, in the 1990s,

when graphical-user-interface two-tier architectures were popular, the

essential skill was mastering Object-Oriented Programming — its iterative,

collaborative design — yet most attention centred on tools like Rational

Rose, the C++ programming language, and frameworks such as Microsoft

Foundation Classes. When the Web arrived, understanding Web architecture

and global-scale caching was crucial, but early hype gravitated toward

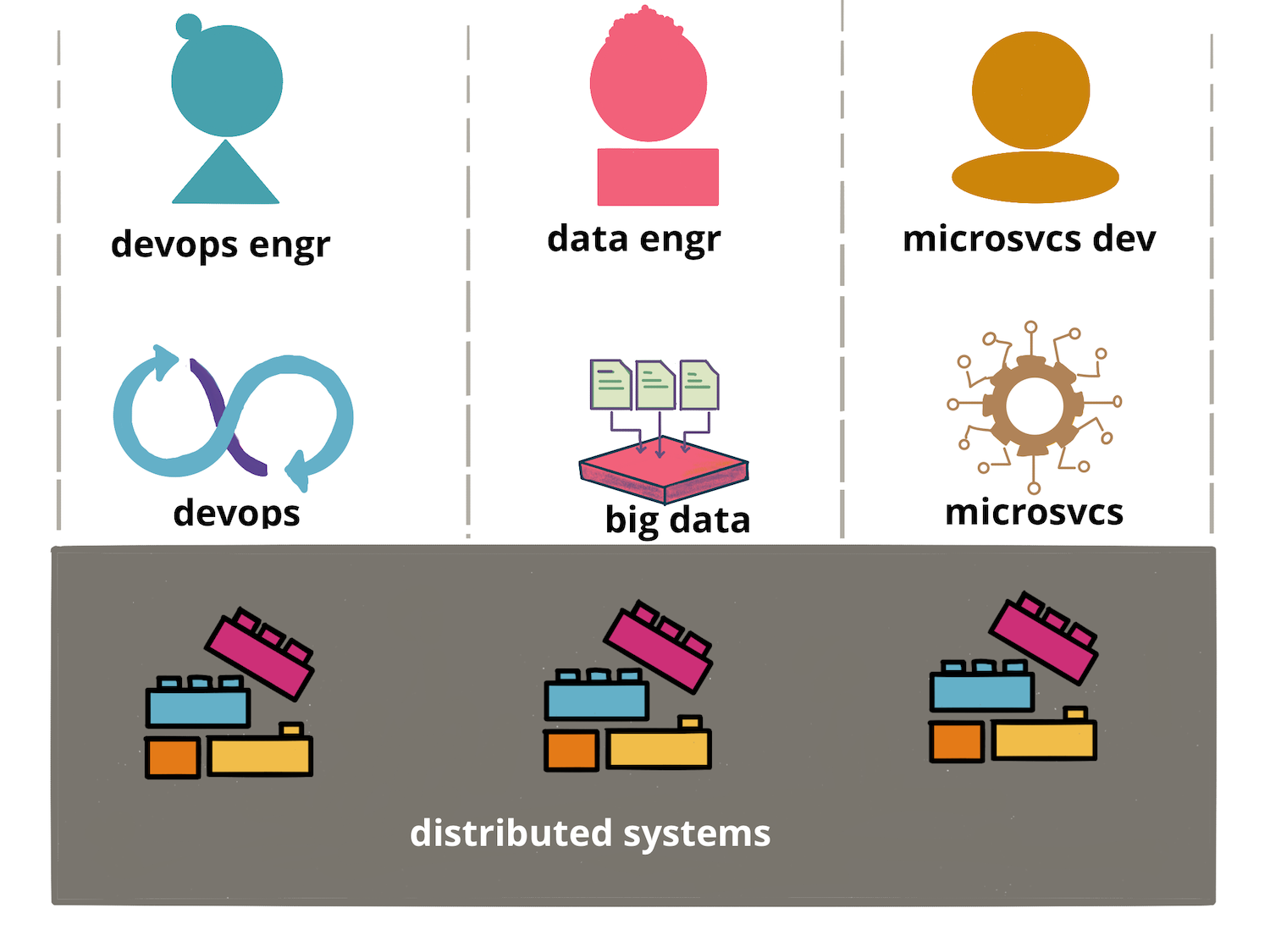

technologies like J2EE. In today’s cloud era, with complex microservice

based architectures, big-data technologies, and expansive DevOps

toolchains, the foundational discipline of distributed systems is often

overlooked while certifications in specific tools dominate.

One of the biggest problems with excessive focus on tools and framework

expertise is when it is cemented into organizational structures. Teams and

organisations get structured around tool expertise, with hardened

boundaries making it difficult for people from one team to acquire skills

from others. Beyond language preferences like Python or Java, you can see

this crystallise in the three most

common software verticals—Application Development, Data Engineering,

and DevOps. Are labels like “Application Development,” “DevOps,” and “Data Engineer” just harmless

shorthand for the work we do? Not really. Once these words harden into career lanes, they

solidify the very silos that the Agile and DevOps culture was meant to dismantle. The

labels become an organisational anti-pattern—turning flow into a series of hand-offs when

it should be a cross-functional sprint. All three share the same

distributed-systems foundations, and anyone who masters those fundamentals

can navigate all three without getting lost in each vertical’s

ever-growing toolset. An expert generalist recognizes this and makes the

deliberate effort to master those fundamentals.

Why does our attention keep drifting toward tool expertise? It isn’t

because people are shortsighted or lazy; it’s because the fundamentals are

hard to see amid the noise. Key ideas hide under stacks of product docs,

YouTube tutorials, vendor blogs, and conference talks. At one end of the

spectrum lie dense academic papers and university courses; at the other, vendor certifications tied to a single product. Connecting

these dots — cutting through the surface to reach the essentials — takes

deliberate effort. One proven aid is the language of patterns: reusable

problem-solution pairs that capture the core principle without the brand

labels. That’s why we belive in investing in exploring, distilling, and

sharing such patterns — so the industry conversation can shift from “Which

tool should I learn next?” to “Which underlying principles and patterns

must I master?”

In our experience, the good grasp of this common language of patterns

and principles also strengthens the product-service partnership. Today

the relationship is often one-way: product teams ship features, service

teams consume APIs. Product teams decide how to certify an engineer as an

expert in a product and service teams aim to do those certifications.

Cloud providers and tool vendors often demand a certain number of

“certified professionals” before they will recognise a service provider as

a competent partner. Yet our experience shows little correlation between

certifications and

competence. The focus on fundamentals pays off when competence is

most needed: an engineer versed in Raft can untangle a Kubernetes

control-plane stall that might puzzle several certified admins, and a

Delta Lake write anomaly can be resolved from first-principles reasoning

about optimistic-concurrency control instead of searching vendor docs.

Once developers across roles share the lingua franca of a system’s

internals, the partnership becomes bidirectional — both sides can

diagnose, propose, and refine solutions together. Better yet, the

engineers who have a good grasp of the fundamentals are able to partner

well with multiple product and platform teams, without needing to have

product specific training for each product

An Example Workshop: Breaking silos and building partnerships

We’ve seen that we can grow the Expert Generalist skill through mentoring

and exposure to varied ecosystems, but one of the consequences of

recognizing Expert Generalist as a first-class skill is that we should

provide training in a similar way that we do with specialist skills. Such

training currently barely exists in our profession. We’ve begun to fill that

gap with workshops that are deliberately focused on developing the Expert

Generalist competence, and we think there should be more training along

these lines.

To help stimulate thinking about this, here’s the details of such a workshop,

aimed at developers to connect Application Development, Data Engineering,

and DevOps. The workshop views this work through a distributed systems

lens, shifting attention to shared building blocks and establishing a

common language across teams. Although this example is developer-centric,

we think the same principle can be adapted just as effectively to any role that

benefits from cross-disciplinary insight.

As we saw earlier, each discipline—Application Development, Data Engineering, and DevOps—faces the same

distributed-systems realities, yet we still lack a shared language. The key challenges of

these systems are the same. They must replicate state,

tolerate partial failures, and still offer consistency guarantees to end users.

A catalogue of patterns around the implementation of

partitioning, replication, consistency, and consensus—that lets every

team talk about the fundamentals without tool-specific jargon is a good start.

One workshop will not turn people into expert generalists, but it does give them a head-start and a clear

window into the challenges their peers tackle every day. That visibility lowers the barrier

to cross-discipline tasks and deepens everyone’s understanding of the products and platforms

they use.

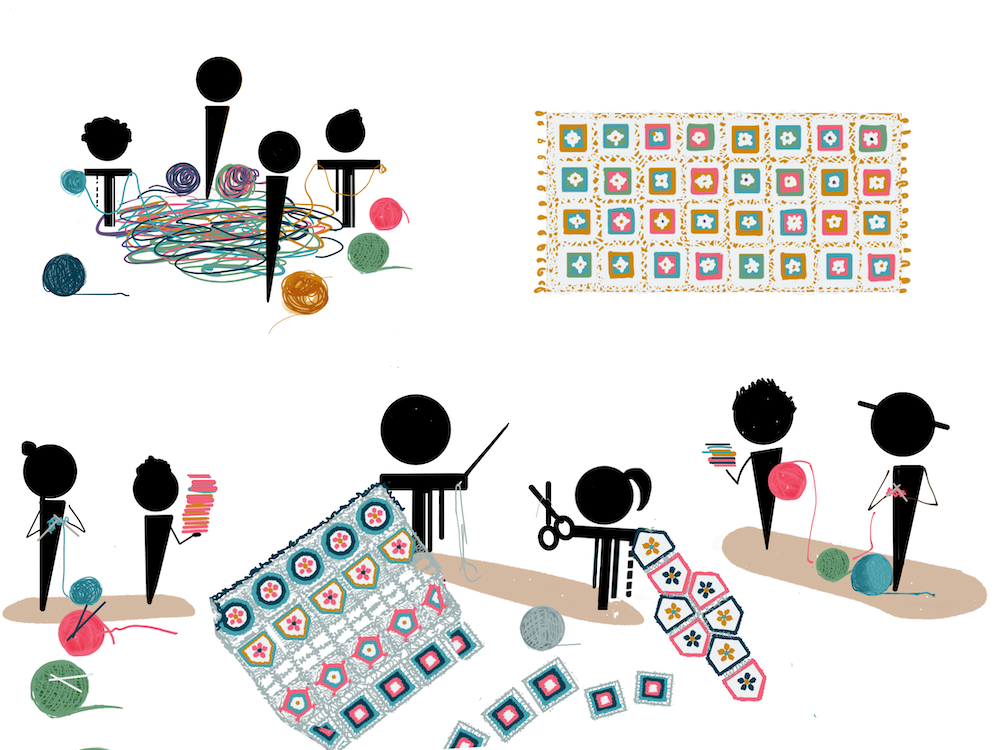

The workshop structure – Building the miniature

One of the challenges in teaching the abstract patterns is that the developers need to do some mental mapping

to connect the pattern to the product in use. This is why we chose an approach to structure

the workshops around specific products, but then focus on the patterns that are most relevant

and using the product as a window into the broader concepts.

The way we structured the workshops to teach distributed-system patterns, is by coding

pocket versions of Kafka, Kubernetes, and Delta Lake. The idea is to pick a flagship product

from each broad area of specialty, and build it step by step. Implementing a flagship system

in just a few hundred lines flips your perspective from ‘a user’ of a product

to ‘a builder’. An important mindset shift. To keep the

exercise grounded in reality, write it in the product’s own language, mirror its file and

method names, and rely on real infrastructure — ZooKeeper or etcd, an on-disk log, live

sockets. The result stays close enough to the original to highlight the pivotal design

choices while still giving you a safe canvas for experimentation. This approach is powerful,

because each target is often open source, the moment the miniature works, you can open the

full codebase on GitHub, recognise the directory structure, and feel confident submitting a

patch. The miniature is not a toy; it is a gateway.

We have three workshops, one for each of the three systems.

Build Your Own Kafka — a miniature written in Java.

We use ZooKeeper for membership and store every message in a single append-only log. Even

on one node you meet the classic fsync dilemma: flush every write for safety or batch for

speed.

Add a second process and you’re suddenly faced with many decisions. You need partition

leader election, quorum acknowledgements, an in-sync replica list, and a high-water-mark

so consumers never read uncommitted data. (A cluster-wide controller comes later, once

multiple partitions appear.) Each mechanism maps to a production feature in Kafka. After

walking this code you recognise why a broker stalls when a replica slows and know exactly

which metric to graph next time it happens.

The takeaway pattern is simple: an append-only log guarded by quorum replication—a design

you will encounter throughout modern distributed systems.

Kubernetes from the Inside Out.

Start by writing a controller that watches a JSON document in etcd, then calls reconcile()

until the local Docker daemon reflects that desired state. Very quickly you have to choose

how to list running containers, queue events, and keep spec and status distinct—exactly

the concerns that dominate the Kubernetes code base.

Add real failure cases and things get tricky. What should the controller do when a

container exits? How does a Postgres container keep its data? Each decision forces you to

reason about restart policies and persistent-volume claims. After that exercise, the dense

Go structs in kube-controller-manager feel like natural continuations of a model you

already understand. The core learning: the power of a declarative desired state converged

by

reconcile loops – the common pattern of orchestration in modern distributed systems

ACID on Object Storage – A miniature Delta Lake.

Create a directory of Parquet files and pair it with a text log; each data change appends

a JSON file naming the new data file. Move this setup into a miniature object store and

every append becomes its own key-value write, with the Parquet file as the value. To

handle concurrent writers, wrap the append in an optimistic lock that retries if the log

tail changes. After a dozen commits start-up drags, so you add a checkpoint file and learn

first-hand why Delta Lake emits one every N transactions. From there, time-travel queries

drop out naturally from the log-plus-checkpoint design. The key takeaway, achieving ACID

guarantees on eventually consistent storage through an immutable transaction log,

optimistic concurrency, and periodic checkpointing – a pattern vital for modern data

lakehouses.

Each miniature leaves you with a concrete pattern — append-only log, reconcile loop,

optimistic commit—that travels well beyond the original context. When the next new tool

arrives, you’ll recognise the pattern first and the product name second, which is precisely

the habit that turns professionals into Expert Generalists.

Expert Generalists still need Specialists

While we’ve spent this article praising the Expert Generalist, we

simultaneously do not deny the value of specialist knowledge. Even the most

skilled Expert Generalist may have to spend valuable time figuring out the

details of how to do something with a new platform. Their knowledge of

common patterns helps them know what to look for, their skill

helps them research faster, but it’s still longer than what a specialist

already knows. Furthermore an Expert Generalist may miss a vital technique

that’s particular to a domain, essentially because the Expert Generalist

doesn’t know what they don’t know – a trap a specialist is far less likely

to fall into. In our experience, a team of Expert Generalists without

specialist knowledge of the core technology of their work will still get the

job done, but will be significantly slower than a team with specialist

skills on board.

The point here is that to be the most efficient, the team needs some

specialist skill. There needs to be at least one deep specialist on a team

for any core technology that the team is working with. But we’ve found that,

providing the team is collaborating effectively, we don’t need very many. Often

one or maybe two people is quite enough.

With someone with specialist knowledge present, a less knowledgeable

Expert Generalist can quickly ask a question when they are faced with a task

that needs the depth. Similarly the specialist should review the work of

less knowledgeable colleagues, so they can spot when folks are taking the

wrong path and show them the better way.

We think it is important to have such a specialist available full-time on

the team. Much of their value comes from being responsive to questions and

issues as they come up. In this situation, the important cost to monitor is

the Cost of Delay – the speed of resolving

questions is much more important that the utilization of the specialists. So

it’s worth having a full-time specialist even if it means they aren’t fully

occupied.

All of this does need everyone involved to have right kind of

collaborative attitudes. The specialist needs to be someone who is keen to

share their knowledge with everyone else on the team, and is approachable

with dumb questions. The Expert Generalists need be comfortable

demonstrating their ignorance, and actually enjoy being told they are doing

something wrong in an unfamiliar environment. All in all there needs to be

plenty of psychological safety around.

And, of course, the people with specialist skills can often be Expert

Generalists themselves, with the specialty being legs in their T.

The flip-side of this is the danger of teams that consist only of

specialists. Things outside their specialty can easily be missed. For

example a data engineering team that’s full of specialist data engineers can

miss anything that isn’t specific to data engineering, such as quality

strategy, release management, and value articulation.

Expert Generalists in the Age of LLMs

Large Language Models and tools based on LLMs are growing in prominence.

We’ve observed that Expert Generalist capabilities are considerably more

valuable with these LLMs. The relationship between Expert Generalists and

LLMs is often similar to that between Expert Generalists and specialists in

a team. Similarly to a specialist, an LLM can rapidly answer questions that

an Expert Generalist will have when working in a new domain. This

significantly lowers the barrier for exploring completely new and unfamiliar

tools, offering a quick way to get started.

An Expert Generalist, armed with

a solid grasp of fundamentals and the knack to master principles and

patterns, can truly harness the power of LLMs. They’re not just asking an

LLM to write code in a new language; they’re able to ask more insightful

questions, critically assess the AI-generated suggestions against their

broader understanding, and adapt those suggestions to fit sound

architectural patterns. Their curiosity discourages them from simply

accepting an answer, but to understand how proposed solutions work – which

is exactly the behavior needed to overcome the unreliability inherent in

LLM-given advice.

We’ve noticed that Expert Generalists approach working with LLMs in a

different way. Rather than looking for “the answer”, they prompt them to

generate questions, explaining mechanisms, and providing examples and even

tools that help explore the underlying mechanisms of an idea.

So, despite the early days of this technology, we think that the rise of

LLMs will further enhance the importance of skilled Expert Generalists, and

thus incentivize enterprises to put more effort into identifying,

and training people with these skills.

Why Organizations Need Expert Generalists

The simplest reason why organizations should pay more attention to Expert

Generalists is the loss of opportunities to staff teams. Finding exactly the

right kind of specialist limits the candidate pool, either from hiring from

outside, or by internal transfers. As long as there’s enough specialist

skill available to assist, Expert Generalists often do as well, indeed often

better, than adding another specialist.

But the benefits of Expert Generalists go further than that. Modern

software systems involve many components, needing collaboration between

specialties to deliver features to production. Too often we see stifled communication, with

folks blocked while waiting on dependent teams to schedule necessary work.

Lots of these queues between teams impedes flow, slowing down the release of

valuable features.

Expert Generalists can unplug the pipes. Sometimes they do this by making

the interaction smoother due to their overlapping skills, sometimes they

know enough to do some of these dependent tasks themselves. Indeed one of the

greatest values an Expert Generalist brings is the ability to Get Things

Done. The customer-focus drives a good Expert Generalist to use their

collaborativeness, curiosity, and skills blend to drive features to

completion. If it requires crossing competency boundaries, they will find a

way to do it. If they need to rapidly acquire some deeper skills, they will do

so. They do risk taking on more than they can chew in the process, but that

ability to close the deal is often imperative in getting critical software

out the door.

Expert Generalists are particularly valuable at

working across the specialist skill boundaries, handling interactions and

filling in gaps.

The ability to see complex systems across their full breadth can be

essential when things go wrong. Faults are often not in the depth of a

single technology, but in the implicit interactions between them. If

specialists can’t see the whole picture, they easily miss what falls between

the gaps.

The presence of Expert Generalists crossing the competency boundaries

can also increase knowledge transfer between competency groups, increasing

everyone’s sympathy for related domains. This mechanism also encourages

specialists to explore the Expert Generalist skill for themselves.

Specialists tend to use their familiar tool in contexts where it doesn’t

make sense. We can’t fault them for that, if you’ve never seen a

screwdriver, you’ll naturally reach for a hammer first. Expert Generalists

are more likely to pick appropriate tools. There is a risk there, of

introducing too many tools into an environment. Sometimes it’s better to use

a familiar-but-inferior tool, than to introduce a complicated tool for a

narrow task that’s a burden once the Expert Generalist moves on. A wise

Expert Generalist will take that factor into account.

The broad view that Expert Generalist develops naturally leads them

towards leadership roles. Crossing specialties encourages them to develop

communication skills, particularly skills on explaining different

disciplines to each other. Collaboration naturally grows relationships with

key people around an organization. Customer-focus, Getting Things Done,

build credibility with business leadership. Organizations that take

deliberate steps to nurture Expert Generalists can reap the reward by

growing technologists with a strategic perspective, without necessarily

pushing them into management tracks.

All that said, despite the fact that we are clearly big proponents of

Expert Generalists, there are downsides. Perhaps the greatest is that

although we’ve found it possible to assess people for their Expert

Generalist skill, it’s a difficult task, often requiring intensive

participation from known-capable Expert Generalists. Years on

the job, quizzes, and certifications are much easier tests to administer

(although we are cynical about how they relate to delivering value).

A team full of Expert Generalists, but without particular skills for the

central domains and platforms they are working on, will be less productive –

at least until the Expert Generalists develop those skills. As we mentioned

earlier, it’s important to have someone with those deep skills on the team,

who can either be specialist in that domain or an Expert Generalist who has

that as one of the legs in their “T”.

All in all, we’ve seen so many of our colleagues develop their Expert

Generalist skill, without the name, and build upon it to be critical parts

of successful technology and business initiatives. They are the people we

have learned from, the people our clients go to with problems to solve and

opportunities to exploit. Our hope with this article is that more people in

our profession (and perhaps others) will start to recognize “Expert

Generalist” as a first-class skill, and put more effort in describing its

characteristics, how to assess it, and how to grow it. We believe that

giving this skill proper recognition can do much to improve the practice of

our profession.

Takeaways

- Expert Generalists share several key traits

- Curiosity

- Collaborativeness

- Customer-focus

- Favoring fundamental knowledge

- A blend of specialist and generalist skills

- Sympathy for related domains

- Teams should blend Expert Generalists with a few key specialists

- Expert Generalist skills are enhanced by LLMs

- Expert Generalists ensure complex tasks get done

- We need to treat Expert Generalist as a first class skill

- Evaluate people’s skill as an Expert Generalist in hiring and

promotion - Develop training just as much as for specialist skills