Metal–organic frameworks are transitioning from laboratory curiosity to industrially viable materials driven by extensive community efforts to enhance their functionality and stability, and by breakthroughs in large-scale manufacturing.

This year’s Nobel Prize in Chemistry went to Susumu Kitagawa, Richard Robson and Omar Yaghi for the development of metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) and demonstration of their potential. This is a big boost for the MOFs community. We want to take this occasion to congratulate the awardees and reflect on the journey that MOFs have experienced from their conception to industrial adoption, with some general remarks about nanoscience along the way.

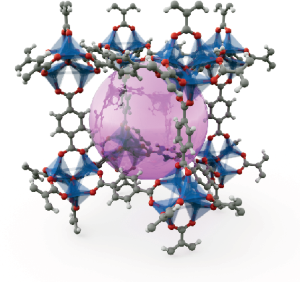

Credit: Thom Leach / Science Photo Library / Getty Stock Images

MOFs are crystalline materials composed of metal ions or clusters connected by organic linkers, forming highly ordered, extended nanoporous networks. These structures have extremely high surface areas — some frameworks exhibit surface areas equivalent to the area of a football (soccer) field contained in a gram-scale sample. The modular and reticular nature of MOFs allows researchers to fine-tune their chemical and physical properties by selecting both the metal nodes and organic linkers. Such synthetic flexibility enables precise control over pore size, shape, and chemical functionality, allowing the frameworks to be tailored for interactions with specific sorbate molecules or active catalytic sites. As a result, MOFs have emerged as versatile platforms for a wide range of applications, including gas storage (for example, H2, CH4)1, gas separation (for example, CO2/CH4, CO2/N2)1,2, water harvesting from air3 and heterogeneous catalysis4. They are also promising candidates for environmental remediation, such as pollutant capture and detoxification5,6.

It might sound obvious, but MOFs are quintessential nanomaterials. The pore size of MOFs is highly variable and can be precisely engineered to range from the nanometre to the sub-nanometre scale. But not all nanoporous materials exemplify the essence of nanoscience as MOFs do. Nanoscience, at its core, is a methodology that allows researchers to understand and control matter at the smallest possible scale. It is this notion of ‘control’ — control in the choice of ligands, control in the choice of the metal centre — that makes MOFs so pleasing and attractive to work with, and so ‘nano’.

Although MOFs have demonstrated remarkable structural and functional versatility, their way to practical deployment has not been straightforward. One of the most persistent issues has been their limited stability. Many early MOFs degrade or collapse under exposure to water, humidity, acidic or basic environments, or elevated temperatures. As a result, their handling has historically been confined to carefully controlled laboratory conditions. In recent years, however, significant progress has been made toward enhancing MOF stability. Advances in metal–ligand coordination chemistry, framework topology, and post-synthetic modification have yielded robust MOFs capable of maintaining structural integrity even under harsh environmental conditions7,8.

Parallel industrial efforts are also advancing the field, with increasing attention to mass production and cost reduction. In October 2023, BASF scaled up CALF-20 (a Zn-based MOF) to several hundred tons per year for Svante Technologies, who wants to use it for carbon capture applications9. Other companies, for instance, Numat Technologies from USA and UK-based specialist manufacturer, Promethean Particles, have also successfully established MOF production at commercial scales10. To reduce the costs, Atoco, a company founded by Yaghi, has been working to synthesize certain specialized linkers in-house11.

Artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted and automated approaches may further shorten the design–synthesis–testing path, reduce the development costs, and accelerate the scalable production of industrially relevant MOFs. Recent progresses combine deep learning and generative models to design new frameworks optimized for specific gases or reactions, as graph neural networks capture the topological and chemical complexity of MOFs with much better accuracy12,13. Integration with high-throughput robotic platforms and automated synthesis systems — such as the closed-loop autonomous materials discovery platform and other experimental robotic systems — now allows AI algorithms to propose, synthesize, and test materials in iterative cycles14. Generative foundational models trained on large materials datasets and large language model-assisted design are emerging to translate chemical intent directly into feasible MOF structures15. Collectively, they might help to accelerate the delivery of more MOFs to the market.

Whenever there is a clear connection between precise nanoscale understanding and macroscopic materials properties, there are the ingredients for a successful nanoscience-enabled technology. MOFs are a beautiful example of this.