Support CleanTechnica’s work through a Substack subscription or on Stripe.

Pricing fertilizer emissions sounds like a recipe for more expensive food, but when the numbers are worked carefully, it turns out to be a policy that cuts emissions sharply while barely moving grocery prices. The reason is simple and counterintuitive. Fertilizer is a large share of farm costs and an even larger share of crop agriculture emissions, but farms only capture a minority of what people pay for food. Changing incentives at the farm gate reshapes behavior quickly, while the effect on the checkout total is damped by the rest of the food system.

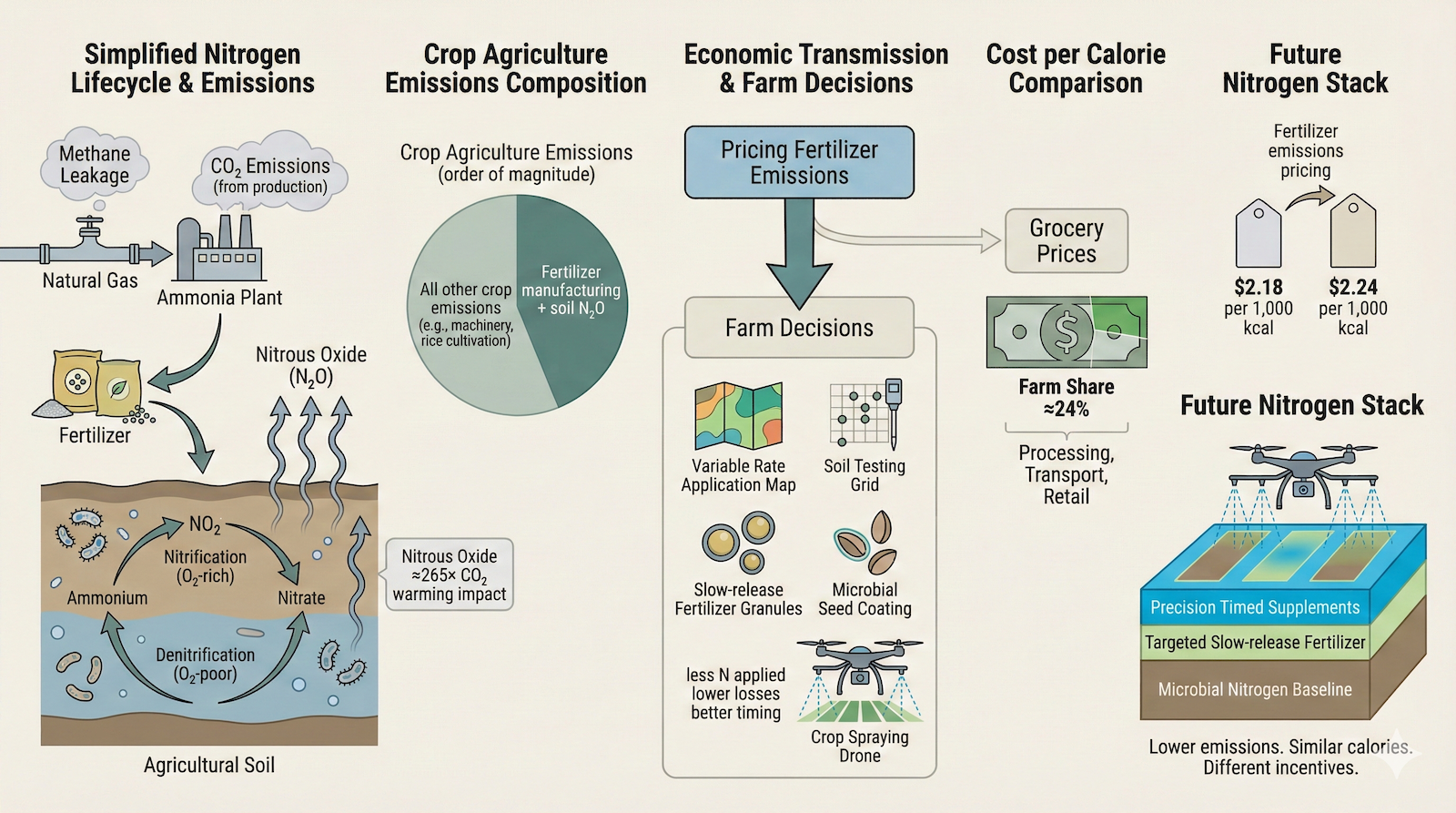

Modern crop agriculture is deeply dependent on nitrogen fertilizer, and nitrogen is where the emissions sit. Roughly half of global crop agriculture greenhouse gas emissions are tied to fertilizer once both manufacturing and field emissions are counted. That makes fertilizer the single largest controllable emissions lever in crop production. It also means that any serious attempt to reduce agricultural emissions has to engage with nitrogen chemistry, not just energy inputs or machinery.

The first part of the problem starts before fertilizer ever reaches a field. Most nitrogen fertilizer begins life as ammonia produced from atmospheric nitrogen and hydrogen. In conventional production, the hydrogen comes from fossil methane through steam methane reforming. Methane is split into hydrogen and carbon dioxide at high temperatures. The carbon dioxide is usually vented to the atmosphere, and upstream methane leakage during gas production and transport adds further warming impact. Even when ammonia plants are efficient, the chemistry itself is emissions intensive because breaking methane and nitrogen bonds takes energy and produces carbon dioxide as a byproduct.

At this stage it is natural to ask whether the solution is simply to decarbonize ammonia itself, either by producing hydrogen through electrolysis using low-carbon electricity to make green ammonia, or by adding carbon capture to fossil-based hydrogen production to make so-called blue ammonia. Both approaches can reduce the carbon dioxide emissions associated with ammonia manufacturing under the right conditions. Green ammonia removes fossil methane from the hydrogen step entirely, while blue ammonia aims to capture most of the carbon dioxide produced during reforming.

In practice, however, neither approach directly addresses the largest share of fertilizer emissions once ammonia reaches the field. Even perfectly carbon-free ammonia still produces nitrous oxide when nitrogen is lost through nitrification and denitrification in soils. From an economic perspective, green ammonia also tends to be more expensive because electricity dominates its cost structure, while blue ammonia remains exposed to methane leakage and incomplete capture unless tightly regulated. As a result, low-carbon ammonia changes the emissions profile of fertilizer manufacturing, but it does not eliminate the incentive to reduce total nitrogen use or improve how nitrogen is delivered to crops. That distinction matters, because it explains why pricing fertilizer emissions reshapes farm behavior even in a world where some ammonia production is decarbonized.

The second part of the problem appears after fertilizer is applied. Nitrogen is biologically active in soils, and plants do not absorb all of what is applied. Microbes in the soil process nitrogen through two main pathways called nitrification and denitrification. Nitrification occurs when soil bacteria convert ammonium into nitrate in the presence of oxygen. Denitrification occurs when other bacteria convert nitrate into nitrogen gases under low oxygen conditions, such as waterlogged soils. Both processes can produce nitrous oxide, a greenhouse gas with roughly 265 times the warming impact of carbon dioxide over a 100 year period. Small losses of nitrogen as nitrous oxide translate into large climate impacts.

These soil processes are highly sensitive to moisture, temperature, soil structure, and timing of fertilizer application. That is why emissions from fertilizer are uneven and episodic. A dry field might lose little nitrogen, while a wet field after heavy rain can emit a large pulse of nitrous oxide. Farmers cannot directly see this gas, but it represents both lost fertilizer value and climate damage.

Globally, agricultural inventories show that synthetic fertilizer nitrous oxide emissions are about 0.7 billion tons of CO2e per year. Total non CO2 emissions from crops at the farm gate are roughly 1.7 to 1.8 billion tons CO2e. That means about 40% of crop farm gate emissions come from fertilizer nitrous oxide alone. When fertilizer manufacturing emissions are added, estimated at about 0.4 to 0.5 billion tons CO2e per year, fertilizer accounts for roughly half of total crop system emissions. No other single input in crop agriculture comes close.

Against that backdrop, pricing fertilizer emissions means putting a cost on the expected greenhouse gases associated with fertilizer production and use. In practice, this would rely on emissions factors. Each kg of nitrogen fertilizer applied would carry an expected amount of nitrous oxide emissions based on agronomic research. Each ton of ammonia produced from fossil methane would carry an expected amount of carbon dioxide and methane related emissions. Multiplying those emissions by a carbon price produces an added cost per kg of fertilizer nitrogen.

This does not require measuring emissions on every field in real time. It relies on default values, with optional credits for practices or products that demonstrably reduce emissions. Economically, it works by raising the marginal cost of excess nitrogen, not by making essential nitrogen unaffordable.

The immediate concern is food prices. To assess that, the first step is understanding how food spending breaks down. In developed economies, farmers typically receive about 24% of what consumers spend on groceries eaten at home. The remaining 76% goes to processing, transport, packaging, retail, and other post farm activities. Fertilizer is only one component of farm costs, even for nitrogen intensive crops.

For staple crops like corn, fertilizer represents roughly 20% to 25% of total production costs when land, machinery, labor, and overhead are included. Using 22% as a representative figure provides a conservative basis for calculation. If fertilizer costs rise by 50% per unit of crop output after accounting for efficiency gains, total farm production costs rise by about 11%. When that farm cost increase is passed through to grocery prices at a 24% farm share, the result is a grocery price increase of about 2.6%.

Looking at calories makes the effect even clearer. In the United States, food at home spending averages roughly $3,100 per person per year. The food system supplies about 1.43 million kcal per person per year. That works out to about $2.18 per 1,000 kcal. A 2.6% increase raises that to about $2.24 per 1,000 kcal, an increase of roughly $0.06. Even in an extreme case where fertilizer costs per unit crop doubled, the increase would be on the order of $0.12 per 1,000 kcal.

These are small numbers at the checkout, but they translate into large incentives on the farm. Fertilizer is one of the largest variable costs farmers face and one of the few they can actively manage year to year. Pricing emissions changes the economics of marginal decisions. Applying extra nitrogen as insurance against yield loss becomes more expensive. Avoiding losses through better timing, placement, and product choice becomes more valuable.

This is where precision agriculture moves from optional efficiency to core cost control. Variable rate application allows fertilizer rates to be matched to soil productivity zones. Yield mapping and soil testing identify where nitrogen actually contributes to yield. Better weather forecasting and in season sensing reduce the need to apply nitrogen far in advance of crop uptake. Each of these practices reduces the kg of nitrogen applied per ton of crop harvested, and pricing emissions increases the payoff for doing so.

Fertilizer chemistry also responds. Slow release and enhanced efficiency fertilizers release nitrogen gradually, better matching plant uptake and reducing losses during nitrification and denitrification. These products cost more per ton than conventional urea or ammonium nitrate, but they reduce both nitrous oxide emissions and wasted nitrogen. When emissions are priced, their higher sticker price is offset by avoided emissions liability and lower total application rates.

Biological nitrogen fixation adds another layer. Engineered microbes applied to seeds or soil can supply a portion of crop nitrogen needs by fixing atmospheric nitrogen directly in the root zone. This does not eliminate the need for synthetic fertilizer, but it can displace 20% to 25% of applied nitrogen in some systems. That reduction allows farmers to reserve synthetic nitrogen for peak demand periods, where efficiency matters most. With fewer total kg applied, it becomes easier to justify higher quality fertilizer products for the remaining share.

Application technology matters as well. Low cost drone spraying and drone seeding reduce the transaction cost of making multiple, small, well timed applications. Traditional fertilizer equipment encourages one or two large passes because each pass is expensive and constrained by soil conditions. Drones decouple application from heavy machinery, allowing nitrogen to be applied when crops need it rather than when equipment can access the field. That reduces losses and emissions while improving yields.

Together, these changes shift fertilizer markets. Total tons of synthetic nitrogen sold may flatten or decline, while the share of premium, high efficiency products increases. Spending shifts from volume to control, from bulk inputs to services, data, and targeted delivery. Farmers spend differently, not just more.

Risk plays a central role. Nitrous oxide emissions and nitrogen losses are not evenly distributed across years. They spike under certain weather conditions, especially wet soils after fertilization. Pricing emissions raises the cost of bad outcomes rather than average outcomes. Technologies and practices that reduce downside risk become more attractive even if average fertilizer spending changes little. This is a key reason adoption accelerates when pricing is introduced.

Distributional effects matter, but they are not unique to emissions pricing. Larger farms adopt precision tools faster because savings scale with area. Mid sized farms often rely on service providers, cooperatives, or custom applicators. Smaller farms face mixed outcomes, with some adopting through shared services and others facing pressure to consolidate. These dynamics exist today and are shaped more by technology costs and market structure than by modest changes in fertilizer prices.

What pricing fertilizer emissions does not do is eliminate fertilizer or threaten food security. Nitrogen remains essential to feeding billions of people. The policy does not target calories or yields. It targets waste, losses, and emissions intensity. It does not require perfect measurement to work. Default emissions factors already create strong incentives at the margin.

When fertilizer is treated as the powerful chemical it is, rather than a cheap commodity, behavior changes quickly. Emissions fall because fewer kg are applied, losses are reduced, and nitrogen is delivered closer to when and where crops can use it. Food prices move only slightly because farm costs are only part of what consumers pay. The math supports this outcome clearly.

Pricing fertilizer emissions aligns incentives with biology and physics. It reduces one of the largest sources of agricultural greenhouse gases without meaningfully increasing the cost of calories. In climate policy, that combination is rare.

Sign up for CleanTechnica’s Weekly Substack for Zach and Scott’s in-depth analyses and high level summaries, sign up for our daily newsletter, and follow us on Google News!

Have a tip for CleanTechnica? Want to advertise? Want to suggest a guest for our CleanTech Talk podcast? Contact us here.

Sign up for our daily newsletter for 15 new cleantech stories a day. Or sign up for our weekly one on top stories of the week if daily is too frequent.

CleanTechnica uses affiliate links. See our policy here.

CleanTechnica’s Comment Policy