Isolation, characterization and compositional analysis of CL-EVs

CL-EVs were isolated from fresh Chinese leek using differential centrifugation, followed by purification and comprehensive characterization (Fig. 1 A). TEM imaging demonstrated that CL-EVs possessed homogeneous spherical morphology with an average diameter of approximately 150 nm (Fig. 1B, C). Zeta potential analysis revealed a surface charge of −14 mV for CL-EVs (Fig. 1D). Western blot analysis showed positive signals for both TET8 and PEN1 in both freshly prepared CL-EVs solutions and a lyophilized powder (Fig. S8). Proteomic profiling identified CL-EVs as containing abundant functional proteins, notably oxidation-related regulators, ribosome-associated factors, peroxidase, thiopropanol oxidase, selenocompound metabolism, and alliinlyase (Fig. 1I). Rigorous quality control was implemented through evaluation of inter-sample quantitative correlations at both peptide and protein levels across all specimens (Fig. S1). Lyophilization was performed to assess CL-EVs stability, yielding dark green lyophilized powders (Fig. 1E). Stability assessment demonstrated comparable vesicle sizes between lyophilized powders (room temperature) and solution-stored (−20 °C) CL-EVs over 4 weeks, with transient minor differences observed at week 1 (Fig. 1 F). SDS-PAGE analysis at day 28 confirmed intact protein profiles in CL-EVs (Fig. 1G). RNase treatment caused comparable band attenuation in both lyophilized and solution groups, indicating equivalent RNA stability profiles across CL-EVs formulations (Fig. 1H). Typical TIC chromatograms were acquired under optimized conditions in both positive (POS) and negative (NEG) ionization modes. LC-MS characterization revealed 17 bioactive components in CL-EVs, including in NEG mode: Adenine, Quercetin, Vanillic acid, Diallyl disulfide,2,5-octanedione, p-Coumaric acid, trans-2,4-Decadienal, 15-hydroxylinoleic acid, 16 − 2,4-Di-tert-butylphenol. POS mode analysis identified Adenosine, Phenylalanine, Caffeic Acid, Cianidanol, Docosadienoic acid, 17-Quercetin, 9,11-Octadecadienoic acid, Allyl [2-propenyl] isothiocyanate. Quercetin was uniquely identified through dual-mode detection. The identified compounds were either definitively characterized or tentatively annotated. Comprehensive metabolite profiles of CL-EVs, including compound identities, retention times, ionization modes, adduct formations, molecular formulae, and m/z values, are systematically catalogued in Fig. S2.

Collectively, these findings demonstrate that lyophilized CL-EVs maintain long-term structural integrity and compositional stability, exhibiting superior storage stability and batch-to-batch reproducibility. Integrated proteomic and LC-MS analyses further revealed that CL-EVs are enriched with bioactive constituents functionally linked to diverse metabolic pathways.

Isolation, characterization, proteomic and LC/MS analyses of CL-EVs. (A) Extraction and isolation processes of CL-EVs. (B) Morphological characterization of CL-EVs by TEM. (C) Particle size and distribution of CL-EVs. (D) Zeta potential of CL-EVs. (E) Lyophilized CL-EVs exhibiting characteristic dark green coloration. (F) Size variation of CL-EVs in lyophilized powder at RT and solution at −20℃ over 0–28 days. (G) Protein content analyzed by SDS-PAGE on day 28 for lyophilized powder and solution-stored CL-EVs. (H) RNA gel electrophoresis results of CL-EVs under different states. (I) Proteomic analysis of CL-EVs. (J) Compounds in CL-EVs identified by LC/MS analyses in negative and positive modes

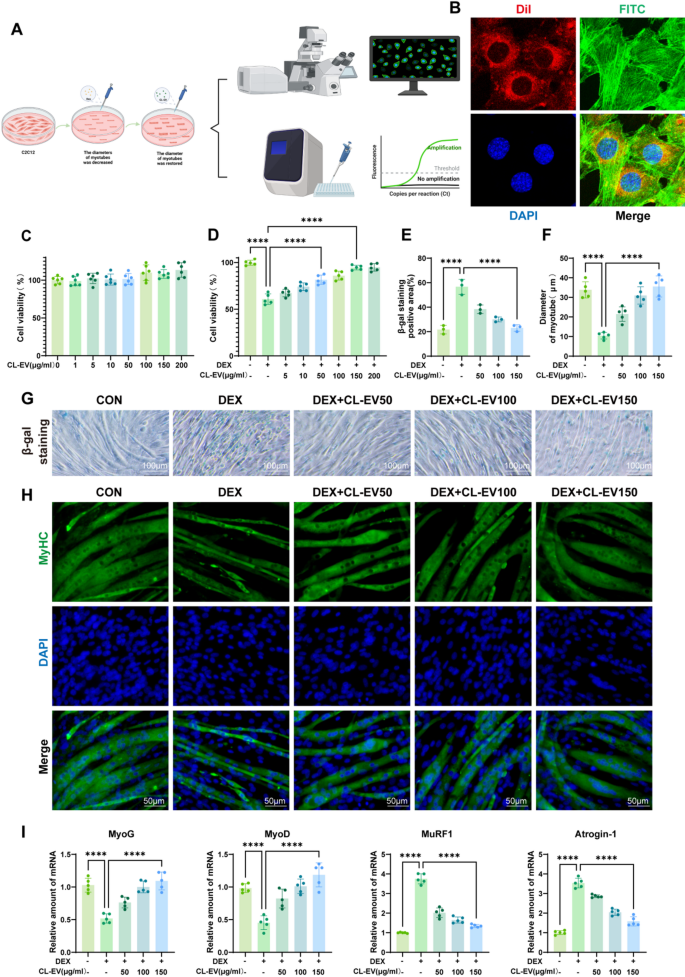

CL-EVs internalization rescued DEX -induced myotube atrophy through cytoskeletal remodeling

To establish the sarcopenia model, C2C12 myotubes were differentiated and subsequently challenged with 100 µM DEX for 24 h (Fig. 3 A). Cellular uptake was confirmed through confocal microscopy imaging of Dil-labeled CL-EVs internalized by C2C12 cells following 6-hour co-culture (Fig. 3B). We established the in vitro model by differentiating C2C12 into myotubes and stimulating with 100µM DEX for 24 h, then treated with CL-EVs concentrations (0–200 µg/ml) for 24 h. CCK-8 analysis revealed that CL-EVs pretreatment (0–200 µg/ml) exhibited no intrinsic cytotoxicity (Fig. 3C), yet dose-dependently mitigated DEX-induced cytotoxicity (Fig. 3D). Dose-response analysis identified 150 µg/ml as the optimal protective concentration, leading to selection of three dosage gradients (50, 100, and 150 µg/ml) for mechanistic investigations.

Senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining, the gold standard for detecting cellular senescence, validated successful establishment of the DEX-induced senescence model (Fig. 3G) [29]. CL-EVs dose-dependently alleviated DEX-induced senescence phenotypes across tested concentrations (Fig. 3E). Myosin heavy chain (MyHC) immunostaining further revealed that CL-EVs treatment significantly preserved myotube diameter compared to DEX-treated controls (Fig. 3 F, H). Myogenin (MyoG), a key myogenic regulatory factor (MRF), orchestrates the initiation phase of myoblast fusion [30]. MyoD regulates myoblast proliferation and differentiation through the AMPK/SIRT1/PGC-1α axis, critically governing myogenic lineage specification [31]. MuRF1, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, mediates proteasomal degradation of contractile proteins during muscle wasting [32]. Similarly, Atrogin-1 has been reported to inhibit Akt-dependent cardiac hypertrophy in mice through ubiquitin-dependent FoxO protein activation [33]. PCR analysis of these four key proteins showed expected trends (Fig. 3I): DEX group significantly suppressed MyOG/MyOD expression while increasing MuRF1/Atrogin-1, which were reversed by CL-EVs treatment. These results indicate CL-EVs could inhibit DEX-induced myotube atrophy in C2C12 cells.

CL-EVs can be internalized by C2C12 cells and promote DEX-induced myotube diameter, ameliorating muscle atrophy. (A) Schematic diagram of in vitro model establishment. (B) Confocal microscopy images of C2C12 cells and CL-EVs (Dil-labeled CL-EVs in red; FITC-stained cytoskeleton in green; DAPI-stained nuclei in blue; Merge shows overlay). (C, D) Effects of CL-EVs concentrations on C2C12 viability; Impact of DEX alone and DEX with CL-EVs on cell viability. “DEX”: 100 µM DEX; “CL-EVs”: CL-EVs at 50/100/150 µg/ml. (E) Statistical chart of β-galactosidase positive area percentage. (F) Statistical chart of average myotube diameter. (G) Representative SA-β-gal staining images. Scale bar: 100µm. (H) MyHC immunofluorescence staining of C2C12 (MyHC labels myotubes, DAPI labels nuclei). Scale bar, 50µm. (I) qPCR analysis of myogenic regulators and atrophy markers. One-way ANOVA analysis and Tukey’s multiple comparison analysis were used in the between-group comparisons. “*”, “**”, “***” and“****” indicate that after Tukey’s multiple comparison analysis, the P-value is lower than 0.05, 0.01, 0.001 and 0.0001

AMPK signaling dysregulation contributed to age-related sarcopenia pathogenesis

Single-cell transcriptomic analysis followed standardized pipelines (Fig. 4 A) involving data integration, clustering, and cell type annotation, with batch effect correction implemented via Harmony algorithm. Rigorous quality control filtering (Fig. 4B) yielded 79,120 high-quality cells for subsequent analyses. Unsupervised clustering revealed 10 transcriptionally distinct cell clusters (Fig. 4D) annotated via established marker genes (Fig. 4C), encompassing myofibers, fibroblasts, basal cells, endothelial cells, and macrophages. Myofiber sub-clustering (6,362 cells, Fig. 4E) enabled age-stratified comparative analysis. Differential expression analysis (genes detectable in ≥ 25% of cells) revealed 5,514 DEGs between age groups. Enrichment analysis of significant DEGs using GO and KEGG databases showed autophagy, cellular senescence, and AMPK signaling pathways in KEGG, with mitochondrial organization and autophagy regulation in GO (Fig. 4F-G). These mechanistic insights implicate AMPK signaling as a pivotal regulator in sarcopenia pathogenesis, mediated through mitochondrial homeostasis and autophagic processes, thereby informing CL-EVs-based therapeutic strategies for mitigating age-related muscle decline.

Single-cell sequencing of sarcopenia clinical samples. (A) Computational workflow for single-cell RNA-seq analysis. (B) Quality control criteria (cells with 300–5000 features, 1000–20000 total RNA counts, mitochondrial RNA < 5% retained, n = 79,120). (C) Classical gene expression patterns across cell clusters. (D) Dimensionality reduction and clustering results (UMAP plot). (E) Myofiber cell clustering analysis (n = 6,362). (F) KEGG enrichment results of differential genes. (H) GO enrichment results of differential genes

CL-EV attenuates DEX-induced sarcopenia signatures in C2C12 Cells: transcriptomic analysis highlights role of AMPK pathway activation

To evaluate the effects of DEX and CL-EV on transcriptional alterations in C2C12 cells, we performed high-throughput RNA sequencing to systematically profile intracellular mRNA dynamics. Volcano plots demonstrated significant differential gene expression across groups. Specifically, 2,423 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) (|log2FC| >1, P < 0.05) were identified between the DEX and control (Con) groups, comprising 1,217 upregulated and 1,206 downregulated genes. In contrast, 198 DEGs were detected between the CL-EV and DEX groups, with 103 upregulated and 95 downregulated genes (Fig. S3A). Notably, a Venn diagram revealed 48 overlapping DEGs between these comparisons (Fig. S3B). Furthermore, hierarchical clustering heatmaps confirmed distinct transcriptomic profiles across groups, with clustering patterns tightly aligned to experimental conditions and no detectable batch effects (Fig. S3C, D). To functionally annotate these DEGs, we conducted KEGG pathway enrichment analysis on upregulated and downregulated gene sets separately. As shown in Fig. S3E, statistically significant pathways (ranked by ascending p-value) are displayed. In the DEX vs. Con comparison, upregulated DEGs were predominantly enriched in ribosome biogenesis in eukaryotes, amino acid metabolism, and cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction. Conversely, downregulated DEGs were associated with HIF-1 signaling pathway, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, AMPK signaling pathway, and mTOR signaling pathway. In the CL-EV vs. DEX comparison, upregulated genes were enriched in autophagy, PI3K-Akt signaling pathway, AMPK signaling pathway, and FoxO signaling pathway, whereas downregulated genes clustered within calcium signaling pathway and TNF signaling pathway. To further explore pathway-level perturbations, Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) was employed. Strikingly, oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) was significantly upregulated in the DEX-induced model group (p < 0.01) but downregulated in the CL-EV treatment group (p < 0.01). Although the AMPK signaling pathway showed no statistically significant changes (P > 0.05), its downregulation in the model group and subsequent upregulation in the CL-EV group collectively suggest that AMPK pathway activation may contribute to CL-EV-mediated mitigation of sarcopenia-related phenotypes (Fig. S3F).

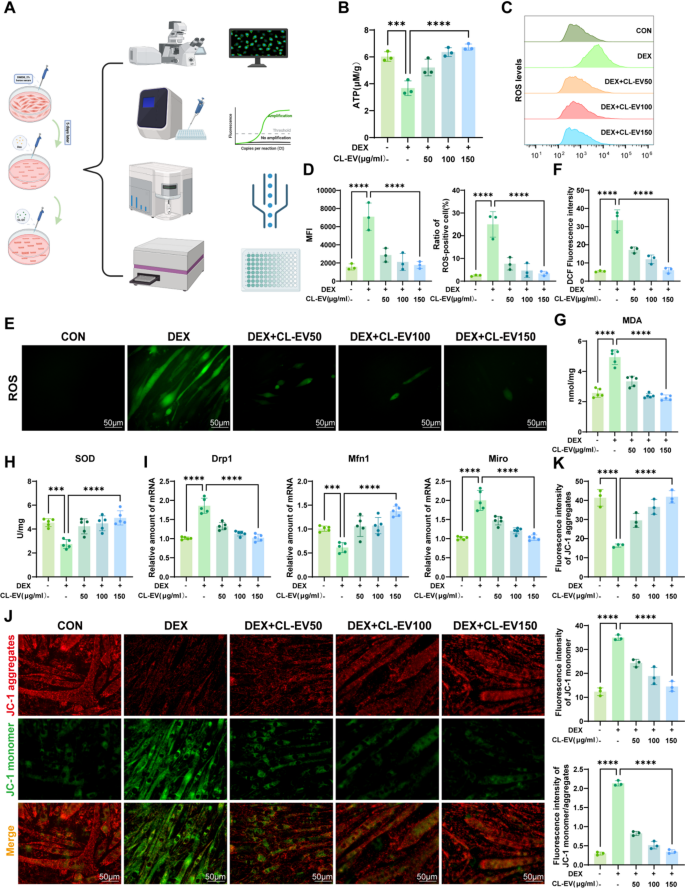

CL-EVs rescued mitochondrial dysfunction of C2C12 cells induced by DEX

Mitochondrial dysfunction is a characteristic of sarcopenic muscle cells, often accompanied by ROS accumulation and loss of mitochondrial membrane potential [34]. As the energy currency of life, ATP synthesis via mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation constitutes the cornerstone of cellular bioenergetics. Therefore, mitochondrial ATP levels reflect functional status, and mitochondrial dysfunction is a key factor in neurodegenerative diseases, metabolic disorders, and sarcopenia [35]. ATP assay showed significantly reduced mitochondrial ATP in DEX group, which was attenuated by CL-EVs treatment (Fig. 5B). Impaired electron transport chain flux increases ROS generation, while compromised antioxidant defenses exacerbate oxidative stress, damaging mitochondrial structure and function [26]. DCFH-DA assay revealed significant ROS accumulation in DEX group, which was mitigated by CL-EVs (Fig. 5E, F). Flow cytometric quantification (Fig. 5 C) confirmed elevated mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) and ROS-positive cells in DEX-treated myotubes, both normalized by CL-EVs intervention (Fig. 5D). We also measured MDA (oxidative marker) and SOD (antioxidant enzyme) levels (Fig. 5G, H) [36, 37]. CL-EVs treatment reduced MDA and increased SOD, alleviating oxidative damage.

Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), a sensitive indicator of outer membrane permeability (MOMP) and structural integrity, closely related to energy metabolism and oxidative stress [38]. To assess mitochondrial effects, we measured MMP using JC-1 staining (Fig. 5 J). DEX group showed decreased JC-1 aggregates (red) and increased monomers (green), indicating MMP loss. CL-EVs restored JC-1 aggregate/monomer ratio, stabilizing membrane integrity (Fig. 5 K). mRNA expression of mitochondrial dynamics genes confirmed CL-EVs maintain mitochondrial dynamics and alleviates DEX-induced dysfunction (Fig. 5I) [39, 40]. These findings indicate CL-EVs ameliorate DEX-induced mitochondrial dysfunction via restoring ATP, scavenging ROS, and recovering MMP.

CL-EVs ameliorates DEX-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in C2C12 cells. (A) Experimental workflow for evaluating CL-EVs’ protective effects against DEX-induced mitochondrial dysfunction. (B) The detection of mitochondrial ATP production in C2C12 cells. (C) Flow cytometric analysis of ROS fluorescence signals. (D) Left: Statistical analysis of mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) across groups; Right: Percentage of ROS-positive cells in different groups. (E, F) Immunofluorescence measurement and qualitative analysis of intracellular ROS contents in experimental groups. Scale bar = 50 µm. (G, H) Quantitative measurements of MDA production and SOD activity. (I) qPCR analysis of mRNA expressions of Drp1, Mfn1, Miro. (J) Immunofluorescence images of mitochondrial membrane potentials (JC-1 assay). Scale bar = 50 µm. (K) Quantitative analysis of mitochondrial membrane potential via JC-1 staining: aggregate fluorescence intensity, monomer fluorescence intensity, and aggregate/monomer ratio. One-way ANOVA analysis and Tukey’s multiple comparison analysis were used in the between-group comparisons. “*”, “**”, “***” and“****” indicate that after Tukey’s multiple comparison analysis, the P-value is lower than 0.05, 0.01, 0.001 and 0.0001

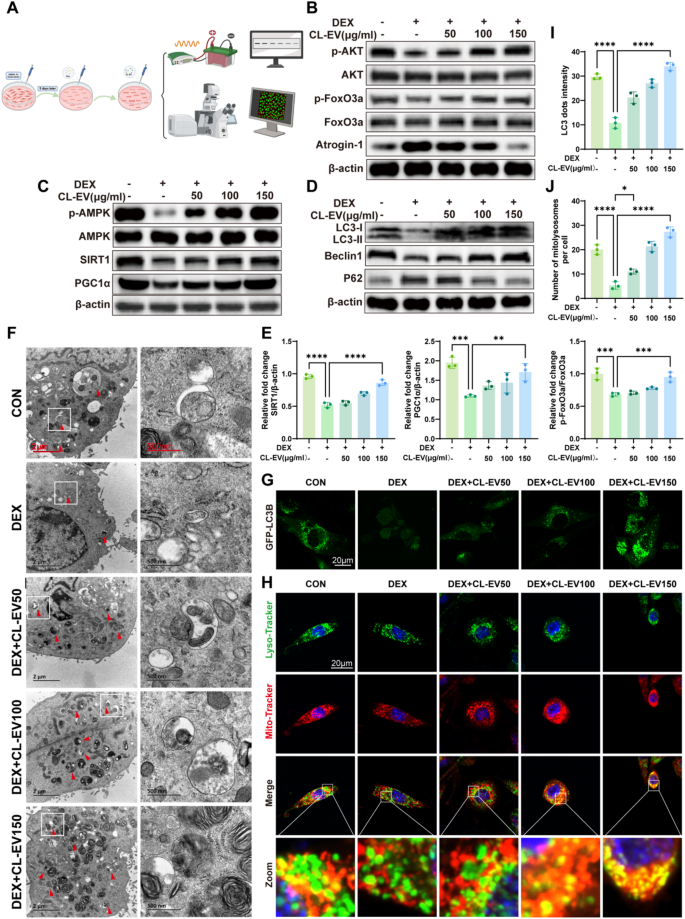

CL-EVs augmented mitochondrial bioenergetics via AMPK activation and Akt targeting to ameliorate DEX-induced muscle atrophy

To elucidate the molecular basis of CL-EVs’ anti-atrophic activity, we focused on key regulatory pathways governing muscle homeostasis. AMPK is a central regulator of metabolic homeostasis, particularly controlling muscle fiber growth and size in skeletal myocytes [41]. Notably, LC-MS analysis revealed high quercetin content in CL-EVs. Previous studies show quercetin activates SIRT1/PGC1α pathway to enhance mitochondrial biogenesis. The AMPK/SIRT1/PGC1α axis is a canonical pathway mitigating mitochondrial dysfunction in sarcopenia. Immunoblotting analysis of the AMPK/SIRT1/PGC-1α axis demonstrated CL-EVs’ pathway-modulating effects: CL-EVs treatment rescued the DEX-induced suppression of p-AMPK/AMPK ratio, SIRT1 expression, and PGC-1α levels (Fig. 6 C). These findings indicate CL-EVs activate the AMPK/SIRT1/PGC-1α axis to drive mitochondrial biogenesis, thereby restoring bioenergetic capacity in atrophic myotubes. To further validate whether the activation of the AMPK signaling pathway is essential for the protective effects of CL-EVs against muscle atrophy, we employed the AMPK-specific inhibitor Compound C for verification. As shown in Fig S9A, compared with the CL-EVs treatment group (DEX + CL-EVs), co-treatment with Compound C (10 µM) significantly inhibited the CL-EVs-induced phosphorylation of AMPK (p-AMPK/AMPK), and subsequently downregulated the protein expression levels of its downstream signaling molecules SIRT1 and PGC1α. Consistent with this, qRT-PCR results (Fig S9B) demonstrated that inhibition of AMPK activity also reversed the upregulatory effects of CL-EVs on the mRNA expression of muscle growth-related factors (MyoG, MyoD), and partially restored the expression of muscle atrophy-related factors (MuRF1, Atrogin-1). These results indicate that AMPK activation is indispensable for the protective effects of CL-EVs, thereby confirming the central role of the AMPK signaling pathway in mediating the alleviation of dexamethasone-induced myotube atrophy by CL-EVs.

Mitochondrial stress (ATP depletion, ROS accumulation) under dysfunction activates mitophagy. AMPK is a key initiator of autophagy in skeletal muscle [42]. Mitophagic flux was assessed via key regulators: Beclin1 (mitophagy initiator), LC3-II/I ratio (autophagosome formation), and p62 (selective autophagy substrate) (Fig. 6D). DEX impaired autophagic flux, evidenced by reduced LC3-II/I conversion, suppressed Beclin1, and accumulated p62. CL-EVs restored autophagic activity in a dose-dependent manner. LC3 (Fig S 4B, D) and P62 (Fig S 4 C, E) immunofluorescence corroborated these findings. TEM was further employed to directly assess autophagosomes in cellular samples across each group. The results showed that the DEX-treated group had lower autophagosome abundance, while CL-EV treatment significantly increased autophagosome abundance (Fig. 6 F). CL-EV-treated C2C12 cells demonstrated significantly increased punctate GFP-LC3 distribution (Fig. 6G, I), further confirming CL-EV-mediated autophagy induction. Concurrently, increased mitochondrial-lysosomal colocalization events following CL-EV treatment suggested enhanced mitophagy (Fig. 6H, J). Selenium-associated proteins in CL-EVs proteome, combined with elemental selenium in Chinese leek, suggest selenium-mediated mechanisms. Selenium supplementation targets Akt/FoxO3a/Atrogin-1 to inhibit proteolysis. CL-EVs activated Akt signaling (Fig. 6B). CL-EVs inhibited DEX-induced activation of Akt/FoxO3a/Atrogin-1 proteolytic pathway. These findings demonstrate CL-EVs alleviates muscle atrophy via AMPK-mediated mitophagy, mitochondrial biogenesis, and AKT-dependent proteolysis inhibition.

CL-EVs ameliorates muscle atrophy by improving mitochondrial biogenesis and mitophagy via AMPK/SIRT1/PGC1α, and regulating Akt/FoxO3a/Atrogin-1 pathway. (A) Schematic diagram of in vitro mechanistic validation. (B) Western blot analysis of Akt/FoxO3a/Atrogin-1 pathway-related protein expression. (C) Western blot analysis of AMPK/SIRT1/PGC1α pathway-related protein expression. (D) Mitophagy-related protein expression. (E) Quantification of protein expression levels by grayscale analysis. n = 3. (F) Representative transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images showing autophagosomes in C2C12 cells (arrows). Scale bars, 2 µm and 500 nm. (G) C2C12 cells transfected with GFP-LC3B plasmid, observed by confocal microscopy for GFP-LC3 puncta (green fluorescent dots) after group treatments. Scale bar, 20µm. (H) Fluorescence images demonstrating mitochondrial (red)-lysosomal (green) colocalization (yellow), with Hoechst nuclear staining (blue). Scale bar, 20 µm. (I) Quantification of GFP-LC3 puncta number per cell (n = 3). (J) Quantification of mitochondrial-lysosomal colocalization points per cell (n = 3). One-way ANOVA analysis and Tukey’s multiple comparison analysis were used in the between-group comparisons. “*”, “**”, “***” and“****” indicate that after Tukey’s multiple comparison analysis, the P-value is lower than 0.05, 0.01, 0.001 and 0.0001

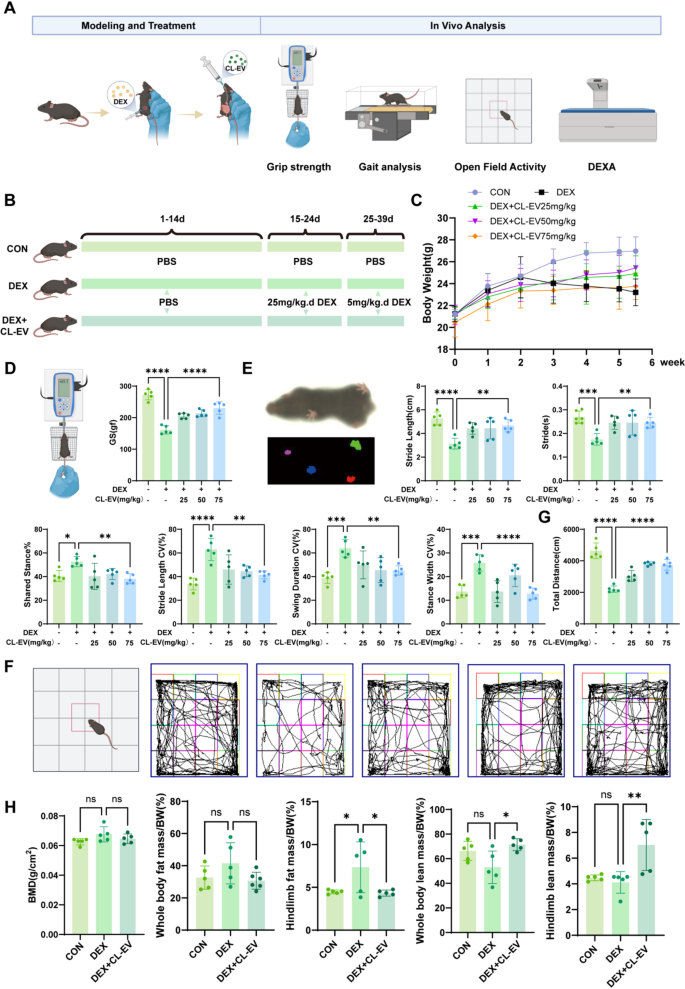

CL-EVs attenuated DEX-induced skeletal muscle atrophy and promotes skeletal muscle mass and function

Correspondingly, we validated CL-EVs’ therapeutic effects on sarcopenia in animal models, with experimental details shown in Fig. 7A. Sarcopenia modeling and intervention protocols are shown in Fig. 7B: 25 mg/kg/d DEX intraperitoneal injection for 9 days to establish model, then 5 mg/kg/d for maintenance. Multi-modal assessment included muscle mass quantification, functional tests, and kinematic analysis to determine therapeutic outcomes. Body weight was monitored throughout, with no significant intergroup differences during weeks 1–2. DEX group showed significant weight loss post-modeling, attenuated by CL-EVs at 25/50/75 mg/kg (Fig. 7 C). Grip strength analysis demonstrated dose-dependent restoration of muscle function, with 75 mg/kg significantly improved strength, though not to CON levels (Fig. 7D).

Comprehensive functional evaluation was conducted per validated sarcopenia assessment guidelines [1, 4, 28, 43, 44]. Gait analysis was performed using DigGait system (Mouse Specifics, USA). CL-EVs groups showed improved stride length and cycle time vs. DEX’s short/rapid gait. DEX group had longer shared stance phase, indicating stability reliance on multi-limb contact. CL-EVs dose-dependently reduced gait variability indices: stride length CV, swing duration CV, stance width CV (Fig. 7E). Open field tests showed CL-EVs groups had more active trajectories and longer travel distances vs. DEX (Fig. 7 F, G). While no intergroup differences in BMD or FM/BW, but CL-EVs attenuated lean mass loss (Fig. 7H). These results indicate CL-EVs inhibits DEX-induced muscle strength loss.

CL-EVs administration significantly attenuated DEX-induced skeletal muscle wasting and enhanced functional capacity. (A) Animal model validation workflow. (B) Schematic of skeletal muscle atrophy modeling and group allocation in mice. (C) Statistical chart of body weight changes from day 1 to 38. (D) Schematic and statistical graph of limb grip strength. (E) Gait schematic and evaluation results (from left: stride length/stride/shared stance phase percentage/stride length CV/swing duration CV/stance width CV). (F) Open field test schematic and movement trajectories. (G) Statistical analysis of open field movement distance. (H) DEXA measurement results at day 38. One-way ANOVA analysis and Tukey’s multiple comparison analysis were used in the between-group comparisons. “*”, “**”, “***” and“****” indicate that after Tukey’s multiple comparison analysis, the P-value is lower than 0.05, 0.01, 0.001 and 0.0001

CL-EVs attenuated DEX-induced skeletal muscle atrophy and promotes myofiber regeneration

Post-sacrifice, three major skeletal muscles (quadriceps, gastrocnemius, tibialis anterior) were collected for comprehensive evaluation (Fig. 8A). Representative muscle size comparisons across groups are shown in Fig. 8B. Quantification revealed CL-EVs increased muscle mass/body weight ratios (Fig. 8C). These results demonstrate CL-EVs’ muscle mass preservation effect. Serum LDH and CK levels were elevated in CL-EVs groups vs. DEX (Fig. 8D, E).

Longitudinal histomorphometric analysis demonstrated DEX-induced muscle mass loss (Fig. S5). Histological analysis of quadriceps, gastrocnemius, and tibialis anterior muscles revealed CL-EVs treatment significantly attenuated DEX-induced reduction in myofiber cross-sectional area (CSA) (Fig. 8F-G). To assess muscle regenerative capacity, immunofluorescence staining was performed on the aforementioned muscle groups. CL-EVs administration markedly increased Pax7 + satellite cell populations (Fig. 8H-I, Fig. S7), indicating enhanced muscle stem cell (MuSCs) pool expansion and regenerative potential. Furthermore, CL-EVs increased dystrophin-positive myofibers. Pax7, a canonical marker of muscle satellite cells (MuSCs), is essential for skeletal muscle myogenesis and regenerative capacity [45]. Dystrophin is located in the endoplasm of muscle cells and is essential for the integrity and stability of the endoplasm [46]. Autophagic flux was systematically assessed across three skeletal muscle groups. IHC staining showed CL-EVs reversed DEX-induced LC3 decrease and P62 increase (Fig. 9A-D, Fig. S6A-D). These findings establish that CL-EVs coordinately mitigate DEX-induced myofiber atrophy while enhancing regenerative potential through MuSC activation.

CL-EVs treatment significantly attenuated DEX-induced skeletal muscle wasting and promoted regenerative capacity. (A) Animal model validation workflow. (B) Representative images of tibialis anterior, quadriceps, and gastrocnemius muscles across groups. (C) Muscle mass/body mass ratios of tibialis anterior, quadriceps, and gastrocnemius. (D, E) Concentration of LDH and CK in serum. (F) H&E staining of muscle cross-sections (gastrocnemius, quadriceps, tibialis anterior). Scale bar, 100 µm. (G) Mean cross-sectional area of myofibers in gastrocnemius, quadriceps, and tibialis anterior. (H) Immunofluorescence staining of gastrocnemius for Dystrophin (green, myofibers), Pax7 (red, satellite cells), and DAPI (blue, nuclei). Scale bar, 50 µm. (I) Quantification of Pax7 + cells in gastrocnemius cross-sections. One-way ANOVA analysis and Tukey’s multiple comparison analysis were used in the between-group comparisons. “*”, “**”, “***” and“****” indicate that after Tukey’s multiple comparison analysis, the P-value is lower than 0.05, 0.01, 0.001 and 0.0001

CL-EVs administration affected the gut microbiota composition and metabolism

The gut microbiota is widely recognized to influence not only intestinal health but also systemic organ functions. Accordingly, fecal samples from control (CON), DEX, and CL-EVs-treated groups were subjected to 16 S rDNA sequencing analysis. Gut microbiome composition was systematically characterized across groups, with taxonomic classification rigorously validated. α-Diversity indices (Chao1, Shannon, and Simpson) were employed to assess microbial community richness and diversity (Fig. 9E). Quantitative analysis revealed no statistically significant differences in α-diversity metrics between CL-EVs and DEX groups. Furthermore, PCoA utilizing Weighted Unifrac distance demonstrated distinct microbial community structures (Fig. 9 F). At the phylum level, Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes constituted the predominant taxa, where the Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio exhibited significant depletion in DEX-treated mice but notable restoration following CL-EVs intervention (Fig. 9G). Additionally, at the genus level, it was found that Muribaculum was significantly reduced after CL-EV treatment (Fig. 9H). Relevant studies indicate that Muribaculum can promote the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines [47]. These findings suggest that CL-EVs treatment mitigates DEX-induced sarcopenia through modulation of gut microbial ecology.

To delineate the metabolic impact of CL-EVs, untargeted metabolomics was employed to characterize gut microbial metabolic alterations. Unsupervised principal component analysis (PCA) and supervised orthogonal partial least squares-discriminant analysis (OPLS-DA) revealed distinct metabolic clustering patterns across experimental groups (Fig. 9I−J). Metabolomics analysis revealed that DEX significantly altered metabolite profiles. Among 481 metabolites down-regulated in DEX vs. Control groups, CL-EV treatment selectively up-regulated 78 metabolites toward control levels, indicating reversal of DEX-induced suppression (Fig. 9 K). Conversely, among 172 metabolites up-regulated by DEX, CL-EVs significantly down-regulated 43 metabolites toward control levels, counteracting DEX-induced elevations (Fig. 9L). KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of DAMs (top 20 pathways ranked by ascending P-values, Fig. 9M) highlighted significant perturbations in histidine metabolism (most pronounced), bile secretion, primary bile acid biosynthesis, GABAergic synapse, porphyrin metabolism, and β-alanine metabolism. Hierarchical clustering of 38 pathway-associated metabolites (Fig. 9 N) demonstrated CL-EVs-mediated metabolic remodeling in gut microbiota. These metabolic reprogramming effects induced by CL-EVs in DEX-challenged mice suggest a potential interplay between CL-EVs-mediated microbiota modulation and metabolic homeostasis.

CL-EVs administration enhances autophagy in DEX-induced sarcopenia and alters gut microbiota and metabolites. (A) LC3 immunohistochemical staining of gastrocnemius at 20x and 40x magnification. Scale bars: 200 µm/100 µm. (B) Quantitative analysis of LC3-positive areas. (C) P62 immunohistochemical staining of gastrocnemius at 20x and 40x. Scale bars: 200 µm/100 µm. (D) Quantitative analysis of P62-positive areas. (E) Fecal 16S rDNA analysis: Alpha diversity indices (Chao1, Shannon, Simpson). (F) β-Diversity PCoA analysis of gut microbiota using Weighted Unifrac distance. (G) Firmicutes/Bacteroidetes ratio. (H) Absolute abundance of Muribaculum. (I) PCA plot and (J) OPLS-DA score plot from fecal metabolomics. (K, L) Metabolomics analysis of CL-EV treatment reversing regulated metabolites in DEX-induced sarcopenia mice. (M) KEGG pathway enrichment (Control vs DEX vs CL-EVs). (N) 38 pathway-associated differential metabolites (Control vs DEX vs CL-EVs). One-way ANOVA analysis and Tukey’s multiple comparison analysis were used in the between-group comparisons. “*”, “**”, “***” and“****” indicate that after Tukey’s multiple comparison analysis, the P-value is lower than 0.05, 0.01, 0.001 and 0.0001